It would be very difficult to improve on the Lamborghini Miura’s lines, but when it came to its dynamics, that was altogether another matter. It may have moved the game on dynamically, but there was still plenty of scope for improvements to how the Miura cornered – and even how it coped with straight lines at very high velocities.

When the team behind the car’s development all started working for Ferruccio Lamborghini, they did so in the hope that he would construct a car with which his company could go racing. But Lamborghini knew that racing was a good way of spending vast sums of money, without necessarily getting much in return. After all, he had customers for every Miura he could make, and it was possible to develop the model on an ongoing basis without the need to resort to getting involved in motor sport.

Lamborghini’s refusal to countenance going racing saw the departure of both Giotto Bizzarrini and Gianpaolo Dallara. That left chief technical officer Paulo Stanzani and development driver Bob Wallace to develop the Miura, and while motor sport was definitely off the menu, that didn’t mean an ultimate version couldn’t be conceived that showed what Lamborghini was capable of.

The project started in 1970, with Stanzani telling Wallace he could do whatever he wanted to produce a Miura that would be successful on the track. Because it wasn’t an official project Wallace was only allowed to work on the project in his own time – although he would have available to him whatever help and materials he needed.

Wallace set about creating a mobile test bed that allowed him to make changes to the aerodynamics and mechanicals with the minimum of difficulty. He tested the car over 20,000 miles, establishing what made the car more usable so that changes could be made to Lamborghini’s production cars.

The development mule was named Jota, supposedly with the J stemming from the Appendix J rules of the FIA – although there isn’t actually a letter J in the Italian alphabet. It was this set of rules to which the Jota would have to adhere if it was ever to race – not that it would ever do so. Interestingly, throughout his article in the August 1971 edition of Car magazine, Doug Blain refers to the car as the Iota, and even as the Miura Privata on account of it being Bob Wallace’s personal toy.

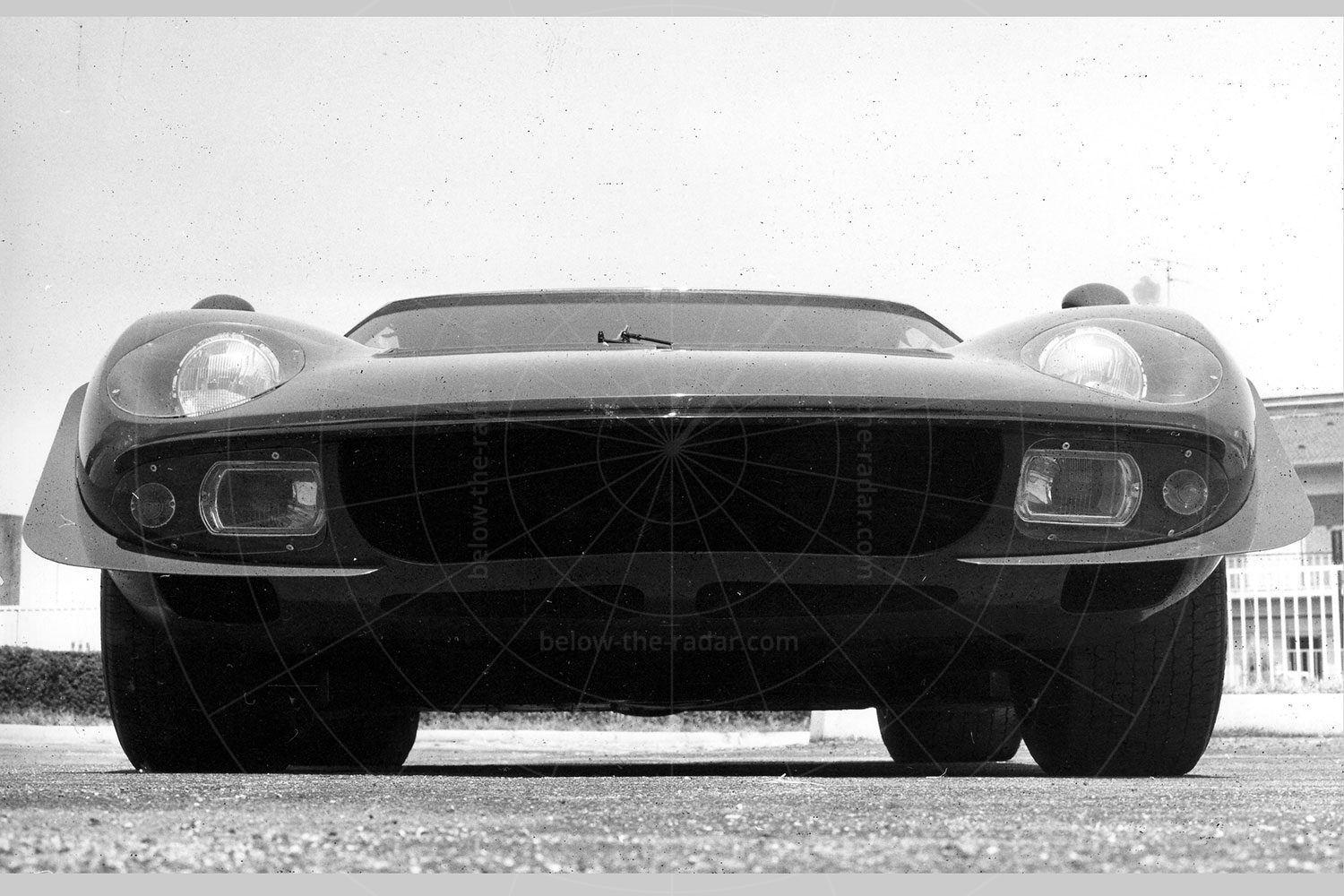

While the car’s bodyshell wasn’t fundamentally changed cosmetically, it did have a mass of skirts and spoilers grafted on to it in a bid to improve the aerodynamics; the headlamps were also faired in. However, it was under the skin that the greatest changes were made. Out went the usual tubular steel chassis and in came a new frame constructed from light alloys that was both stiffer and lighter.

The suspension design was also altered significantly, one of the key characteristics being that it was fully adjustable to allow for experimentation of settings. Brakes were uprated to ventilated discs all round and 15-inch wheels were chosen because they were state-of-the-art at the time. At the front these were nine inches wide while at the rear they were 12 inches across, shod with low-profile Dunlop racing tyres. With its stiffer bodyshell and sharper suspension, the Miura’s handling was transformed – especially when the revised powerplant was taken into account.

To allow the chassis to be fully exploited, the engine was heavily revised to liberate as many horses as possible. With a compression ratio raised to 11.5:1, a spicier camshaft, dry-sump lubrication and open exhausts, the engine was taken about as far as it possibly could be, while still remaining relatively tractable. The whole ensemble was topped off with a quartet of Weber 46 IDL carburettors running without filters. The result was a peak power output of 440bhp at 8500rpm, which when combined with a reduction in kerbweight to around 880kg (nearly 250kg less than the Miura S), meant the car’s performance was nothing short of sensational. Not only could it despatch the 0-62mph sprint in just 3.5 seconds, but it was also capable of achieving 190mph with ease. More impressively, this figure represented a specific power output of 110bhp per litre – no mean feat for a normally aspirated engine at the time.

Constant references to this car and the fact that Lamborghini ought to race it eventually led to a dictat being issued that the car should be sold. It was disposed of through one of Lamborghini’s Italian dealers in 1972, to a particularly insistent customer. But it seems the buyer had more money than driving skill, and the car was promptly destroyed in a high-speed crash.

The Jota inspired a limited run of SVJ ‘replicas’ officially produced by Lamborghini, as well as various other one-offs produced later on. However, the SVJ wasn’t nearly as highly developed as the real thing, as it was little more than a spiced up standard Miura that was far more civilised than the Jota. But the story doesn’t end there as one wealthy (and very patient) enthusiast spent 15 years creating as accurate a Jota replica as he could.

With the project finished in 2006, well known Lamborghini nut Piet Pulford created his Jota facsimile with the help of Bob Wallace to ensure as high a degree of accuracy as possible. Based on an early P400 sourced from the US, the work was carried out in the UK by the late Chris Lawrence of Wymondham Engineering along with Roger Constable of The Car Works. With so much time and money poured into the project, it’s unlikely anything more accurate will ever be produced – and as Bob Wallace commented to Octane magazine when he saw the finished article: “The workmanship is probably better than mine was on the original”.

| Vital statistics | |

|---|---|

| Produced | 1970 |

| Number built | 1 |

| Engine | Mid-mounted, 3929cc, V12 |

| Transmission | Five-speed manual, rear-wheel drive |

| Power | 440bhp at 8500rpm |

| Top speed | 190mph + |

| 0-60mph | 3.5 seconds approx |