Car makers are forever merging segments nowadays. Whether it's a convertible-SUV, a coupé-SUV, an MPV-estate or God knows what else, there are niches within niches. But for some unfathomable reason, no major car maker offers anything that drives on land and water, despite the fact that off-roaders are big business. And when it comes to off-roading, an amphibious car must surely be the ultimate. Talk about a missed opportunity. Or perhaps not, because in the 1960s Hans Trippel reckoned there was an untapped market for amphibious cars, and it was one that he was keen to exploit.

Trippel had been a great exponent of amphibious cars for most of his career in car design and engineering. As early as 1934 he had come up with the four-wheel drive SG6, which was also amphibious. Hitler found out about the SG6 and he quickly realised just what a useful vehicle it might be, so he recruited Trippel to build amphibious cars in Bugatti's Molsheim factory, as part of the war effort once hostilities broke out in 1939.

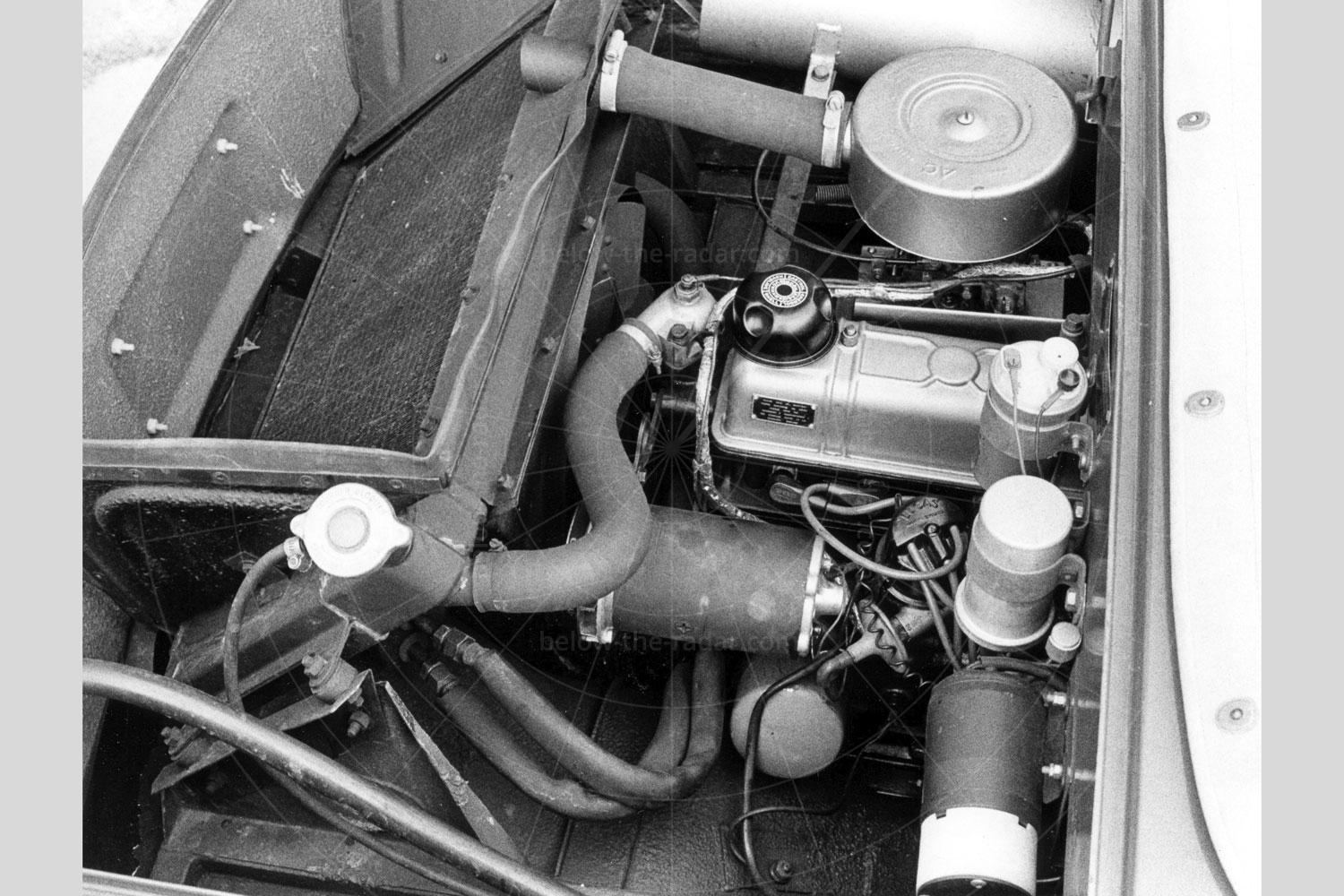

With the war over, Trippel continued with his quest to perfect a car that could be sold in the mainstream market, and which was as (in)capable on water as on land. By 1959 he was ready to unveil it in prototype form. Called the Eurocar Alligator and first shown at that year's Geneva Salon, this floating car was powered by a 34bhp Austin A35 948cc A-series engine, but it wasn't ready for production just yet. Within a few months, Triumph unveiled the Herald with a more powerful (39bhp) 1147cc engine, and Trippel knew that this was just the motive power that he'd been looking for: compact, reasonably light, cheap to buy and tough.

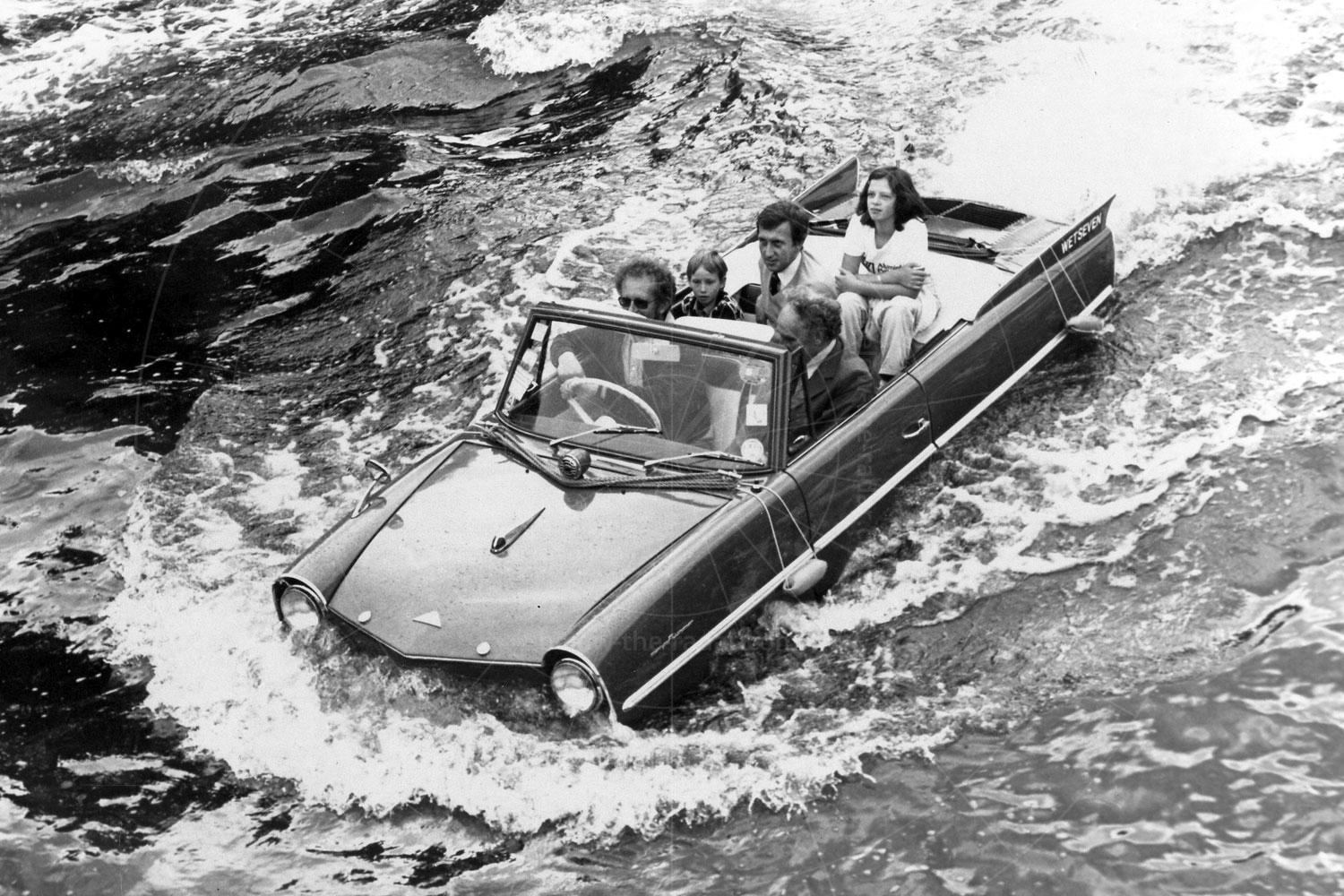

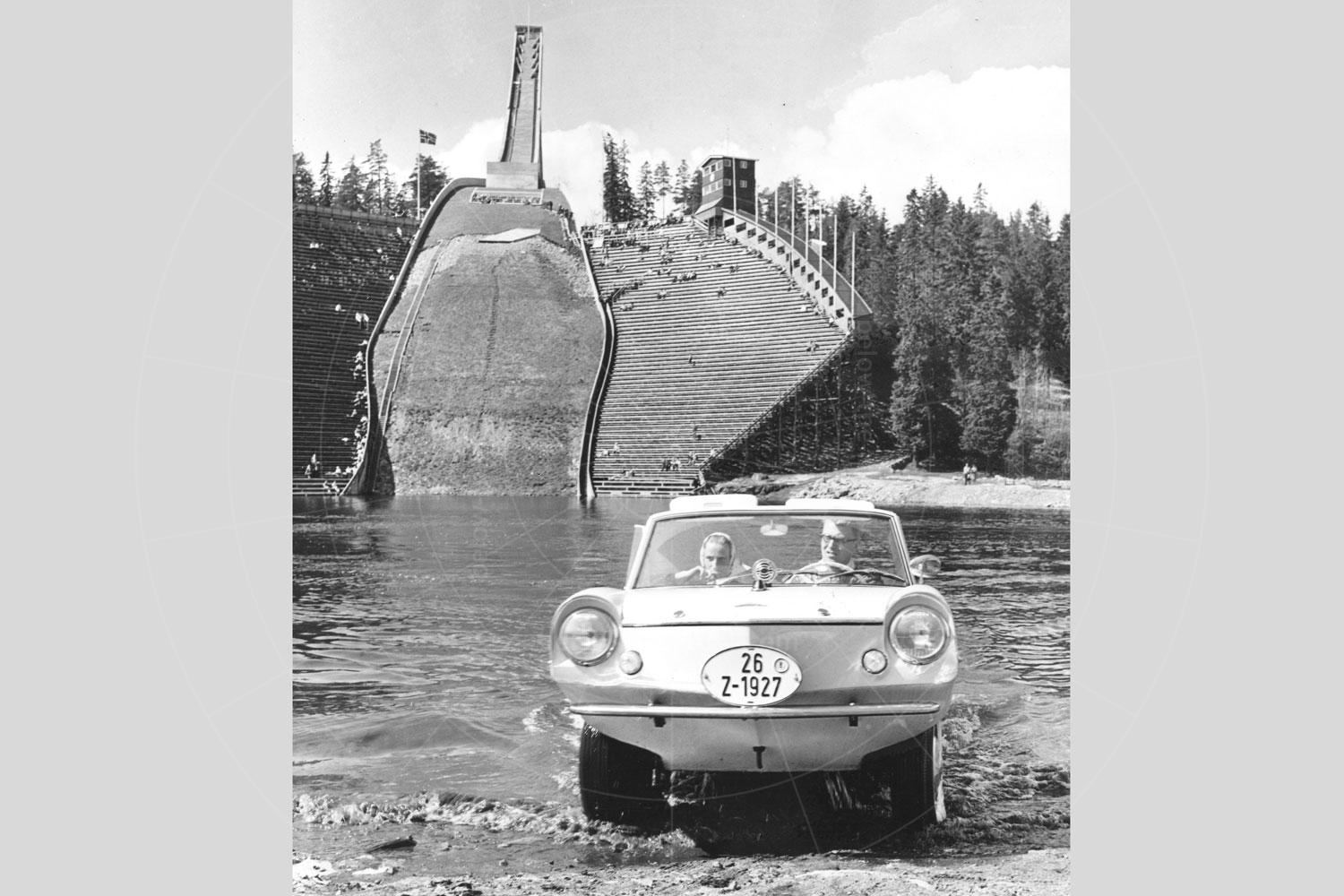

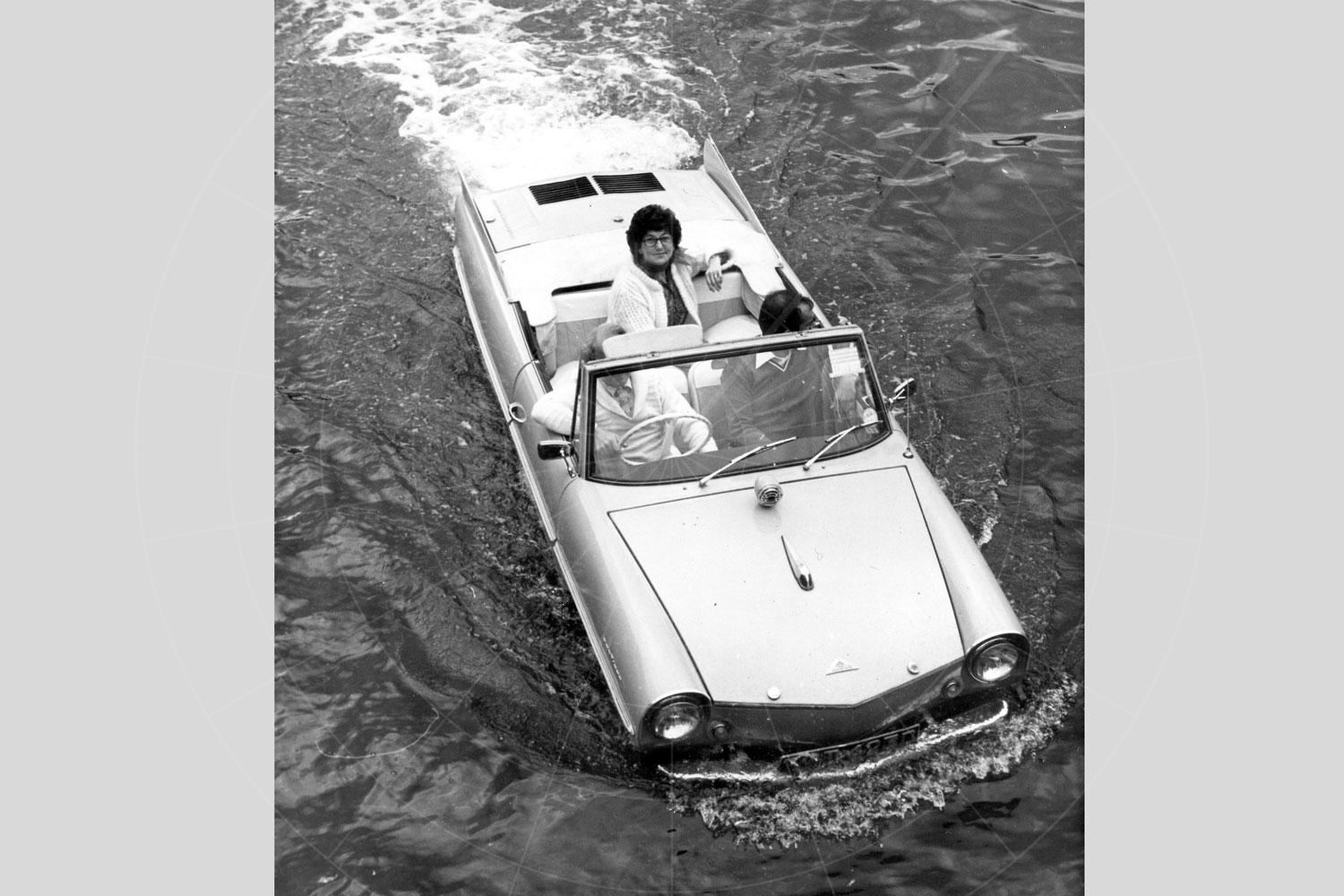

Trippel persuaded the German government that the creation of a mainstream production amphibious car was a tremendous export opportunity, so millions of deutschmarks of taxpayers' cash were ploughed into the car's development. After a couple of years of re-engineering the Eurocar with Triumph power, Trippel was finally ready to show his updated floating machine. Unveiled in production-ready form in 1961 as the Amphicar 770 (7 knots in the water, 70mph on land) and priced at around DM10,000, or twice the cost of a Volkswagen Beetle, this wasn't going to be the easiest sell, but Trippel wasn't going to let that hold him back.

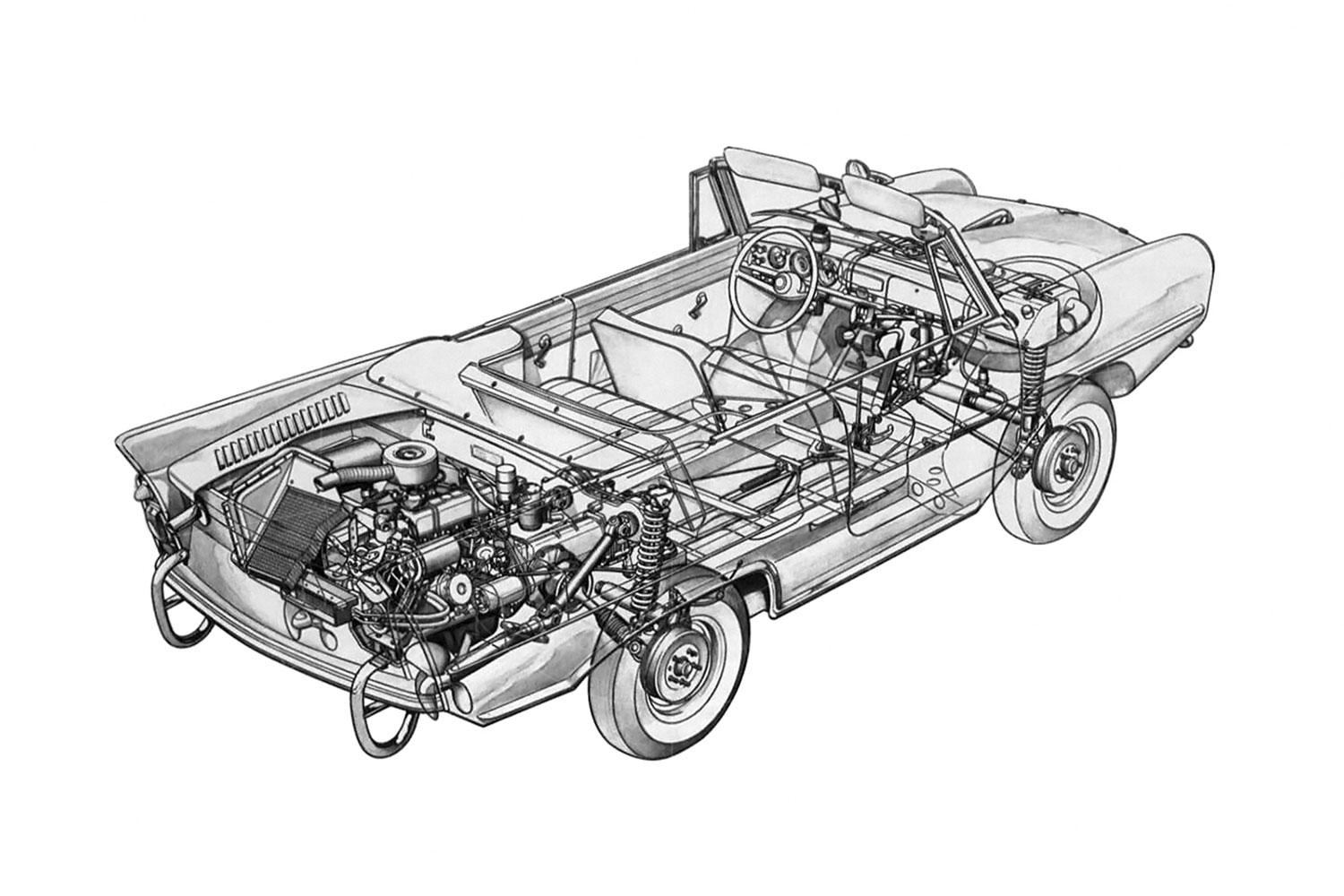

It wasn't just the Amphicar's price that put off potential buyers (apart from the fact that not many people needed a car that could swim…), but the ungainly looks were also something of a turn-off. The Amphicar's ground clearance emphasised the upward-sloping underside at the front, and while the huge fins were á la mode in 1959, by the time the Amphicar reached production they were decidedly passé. Supposedly the tallest fins of any production car ever made, thanks to the generous ground clearance, they were essential to stop water pouring through the louvres in the engine bay cover, and flooding the engine.

If the looks were awkward, the driving experience was even more so. Arguably better on water than on land, or at least less terrible, the Amphicar was slow (0-60mph took a faintly ridiculous 43 seconds), with handling that was equally vague whether sailing or driving. It didn't help that the Amphicar was so heavy; despite glassfibre being all the rage, Trippel insisted on sticking with steel. Not just regular-thickness steel either, because this wouldn't withstand the constant battering of big waves, so extra-thick panels were used instead. This worked wonders for the Amphicar's rigidity, but it didn't half make it hard work to drive, things compounded by the rearward weight bias; the weight distribition front:rear was 40:60.

When Autocar tested an Amphicar in August 1963 it was surprisingly positive: ‘The suspension, trailing links all round, gives a smooth ride and is well damped. There is little road noise. The Amphicar would be very quiet if it were not for the noise of the big fan, coming out of the poop deck louvres.

‘Fifty was a restful and pleasant cruising speed. No opportunity occurred to try for a maximum, but this is stated to be 75mph, which seems possible. The shape for going through water and the smoothness of the bottom are not exactly aerodynamic, but they must help the car through the air.

‘In normal motoring the handling is good. The gear changes involved very long and heavy movements, with a little vagueness, while the steering is spongy but accurate. The weight distribution and the high ground clearance naturally cause oversteer in normal conditions, and in fast cornering there is considerable roll. A car which is a land-marine compromise cannot be a gran turismo or sports two-seater, but for ordinary motoring it is a pleasant one.’

On 16 September 1965, two Amphicars set off from Marble Arch in London, to drive to the Frankfurt motor show, crossing the English Channel along the way. The two cars were provided by Amphicar, and they set off at 5.30am, arriving at Dover two hours later. Having checked radios and life jackets, and that the requisite bungs were in place, the cars entered the relatively still water at 8.50am. But having passed the harbour entrance the scale of the task became evident, with force 3 winds initially, rising to force 6 later in the day; the crossing was scheduled to take six hours.

Within an hour three nautical miles had been despatched, increasing to 6.5 nautical miles after two hours. Then disaster struck at 1.30pm, with one of the cars conking out thanks to water getting into the electrics. There was only one thing for it: the other car had to tow the stricken vehicle to France. As if this wasn’t enough, the 10.5-gallon fuel tank wasn’t big enough to undertake the entire crossing, so the Amphicar had to be refuelled at sea, which meant dropping the roof down and feeding the nose-mounted tank via a snorkel that had been set up specially. At 4.30pm, seven hours and 20 minutes after leaving Dover, the two Amphicars landed at Calais, where the broken-down car was fixed by drying out the electrics and giving the engine a quick service.

Trippel hoped to build 20,000 Amphicars each year, but sales never even got close to such volumes. In hindsight such a prospect was fanciful; the Amphicar was too compromised and expensive to sell in big numbers. Production started at the end of 1960, but within three years it had stopped. Over the next couple of years more Amphicars were produced from left-over parts, but it would be 1968 before the final Amphicars were sold new. It didn't help that the US authorities tightened up the rules for amphibious car construction and use in 1967, and the Amphicar fell foul of the new legislation. In the end just 3878 Amphicars were made, about 90% of which were sold in the US. Just 97 right-hand drive examples were made, mainly for the UK, where the car was listed at £1073.