Aston Martin shooting brakes aren't that unusual, with at least a couple of dozen different examples having been created since the 1960s, some of which have enjoyed more fame than others. Undoubtedly the best-known Aston estates are the DB5s and DB6s converted by Radford when they were new. Less familiar is the trio of DB6 shooting brake conversions carried out by FLM Panelcraft, which also worked its magic on just one DBS; the one you see here.

This car, chassis DBS/5730/R, was originally converted for a Scottish laird who ordered it from London-based Aston Martin dealer HR Owen. It’s claimed that once the car had been built and word had got out of its existence, HR Owen was approached by several more prospective buyers, interested in snapping up further examples. One can only assume they were interested up to the point where the subject of money cropped up, because the conversion work on the DBS is reputed to have cost as much as £10,000 – when the base car was listed at ‘just’ £5717.

Such a disproportionate cost clearly wasn’t an issue for the laird who ordered it; nobody knows who he was, but it seems he wanted something ultra-stylish and fast to carry his fishing tackle around his estate. Just in case he had a particularly good day emptying the streams and lakes, he commissioned a bespoke roof rack as part of the conversion. With its chromed steel tubing and slatted wood there’s no doubting it’s as nicely made as the rest of the car, but things get very noisy with it in place at speed. Besides, such extra carrying capacity is hardly needed when aft of the seats there’s now so much carrying capacity.

The conversion itself is very neat, with the back seat split in half, each section folding forward independently once its retaining bolt has been released. As the back rest flips forward, a panel slides down behind it, to maintain a flat load bay; it’s a very neat solution.

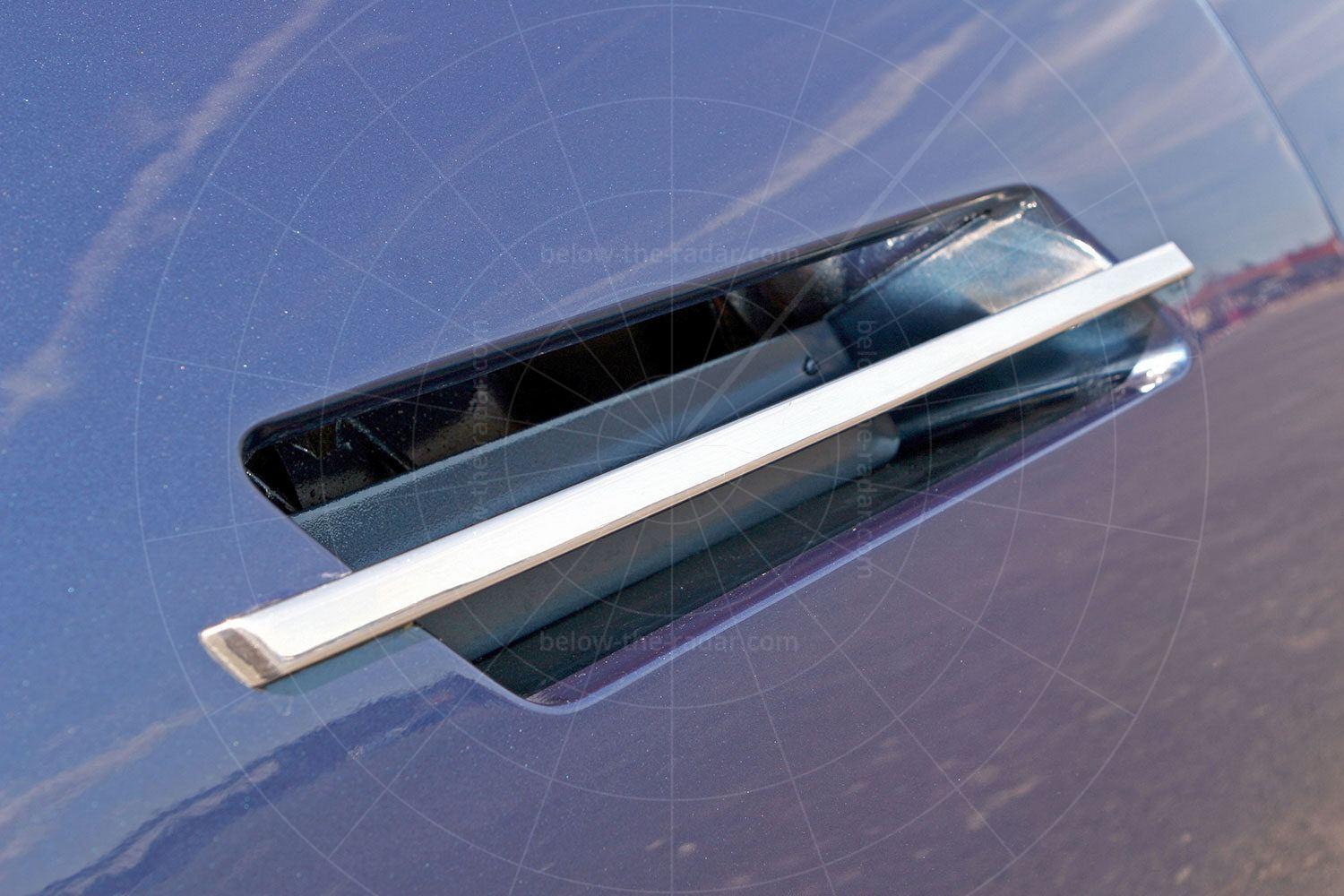

While the interior is neatly resolved, it’s nothing compared with the exterior, which is superbly finished. The coke-bottle curve over the rear wheelarch has been retained, dictating the side window line; while most Aston Martin shooting brakes feature four pillars along each side, this one sticks to just three and looks all the neater for it. Whereas some other conversions address only the fresh metal aft of the doors, using a fill-in panel above the door glass, Panelcraft ditched the original plunging window line altogether, constructing a new window frame instead. It’s a much neater solution as the glasshouse is seamless; it also apes the original chrome-trimmed glass of the original.

In typical seventies fashion there’s a vinyl roof; at first glance it’s easy to assume it’s there to hide a join, but that’s unlikely. The reality is that Panelcraft probably started from scratch with the roof, rather than extending what was already there, so it’s unlikely there’s any join to hide. Less impressive are the parts bin tail lights, as found on various kits and specials of the time; it wouldn’t have taken much more imagination to retain the Aston Martin units. Aside from the fresh tail lamps, all the Aston’s bodywork changes are above the rear wing line, although a bespoke fuel tank had to be made, which sits above the rear axle.

When it first left Panelcraft the DBS was finished in a particularly vivid shade of metallic green, which was quickly changed to red, which by 1980 had changed once again to the discreet dark metallic blue shown here. Surprisingly little is known about this car’s very early history, with the man responsible for building it also receiving few column inches during his life or indeed afterwards. The artisan responsible was John Trowell, who started at James Young in 1948 as an apprentice blacksmith, staying at the company until it was taken over by Jack Barclay in 1967. At this point he moved to FLM Panelcraft, which was staffed largely by ex-James Young employees. By the time Trowell joined FLM Panelcraft he was already an experienced and established panelbeater, capable of achieving amazing things with metal. He could work quite happily in steel as well as aluminium – or even copper as one Saudi prince requested when his stretched Volvo 760 was getting the full treatment in the 1980s.

Trowell was a remarkable man, who rarely sketched anything out, preferring instead to work things out as he went along. He was the father-in-law of ex-Panelcraft trimmer Kevin O’Keeffe, who comments: “John ended up as a director of FLM Panelcraft and there’s no doubt he was one of the company’s greatest assets as his abilities were nothing short of remarkable. While he was at James Young, one Frenchman wanted an all-steel body for his Silver Wraith and John just built one, indistinguishable from the alloy version. He even drilled holes in the structure, to reduce the weight, without compromising the structural integrity. Where John was concerned, anything was possible, so it’s no surprise that he was given the responsibility of creating this one-off DBS estate”.

Panelcraft had started out by restoring pre-war Rolls-Royces and Bentleys, when towards the end of the Sixties it invested in a dozen very tired Phantom I hearses. The company set about rebodying them as boat-tailed roadsters, charging Trowell with rebuilding the engines and creating fresh bodyshells to fit on to the chassis. With those rebuilt and despatched, Panelcraft set about creating limited production runs of estate conversions, including the Rover P6 (for HR Owen), along with BMW and Mercedes estates for Crayford. At a time when factory-built luxury estates weren’t available, the cars proved popular among those who could afford them, so it was no surpise that HR Owen turned to Panelcraft when it was asked to commission the DBS estate.

Despite John Trowell’s undoubted genius, he probably couldn’t have worked out the weight distribution of his finished conversions. However, he seemed to have a very good idea of what would work because the estate drives pretty much the same as any conventional DBS. With its automatic gearbox mated to a 3996cc straight-six engine, performance is brisk rather than startling, but it’s the sound that’s addictive; it’s far more throaty than you’d expect.

Fire up the engine and it quickly settles to a burbly idle; accelerate through the gears and it’s hard to tell just how many cylinders are under the bonnet, such is the noise. It would be easy to mistake it for a V8, especially as the revs and road speed rise, but there’s definitely just a sextet of combustion chambers at work. Because this car wasn’t built to Vantage spec there are just 282 horses doing their bit. That may sound a lot, but with a kerb weight (in coupé form) of 1706kg, there’s just 165bhp per ton on offer. Things aren’t helped by the Borg-Warner three-speed automatic transmission, which not only saps power but also makes for jerky progress in stop/start traffic.

When the DBS6 was new, buyers could choose between a Vantage-spec edition or the less powerful version, as seen here. Although the Vantage came with three twin-choke Webers providing 325bhp, it cost the same as the lesser offering, with its trio of SUs and some 13% less power. When a DBS was ordered, it was also possible to specify a five-speed manual ZF gearbox for the same price as the three-ratio slushmatic; enthusiast drivers would opt for the latter, but our Scottish laird clearly preferred his car to swap ratios for him.

The unique car pictured was sold by Bonhams in May 2012, for a hefty £345,000 including buyer's premium – compared with a ridiculously low pre-sale estimate of just £50,000-£70,000.