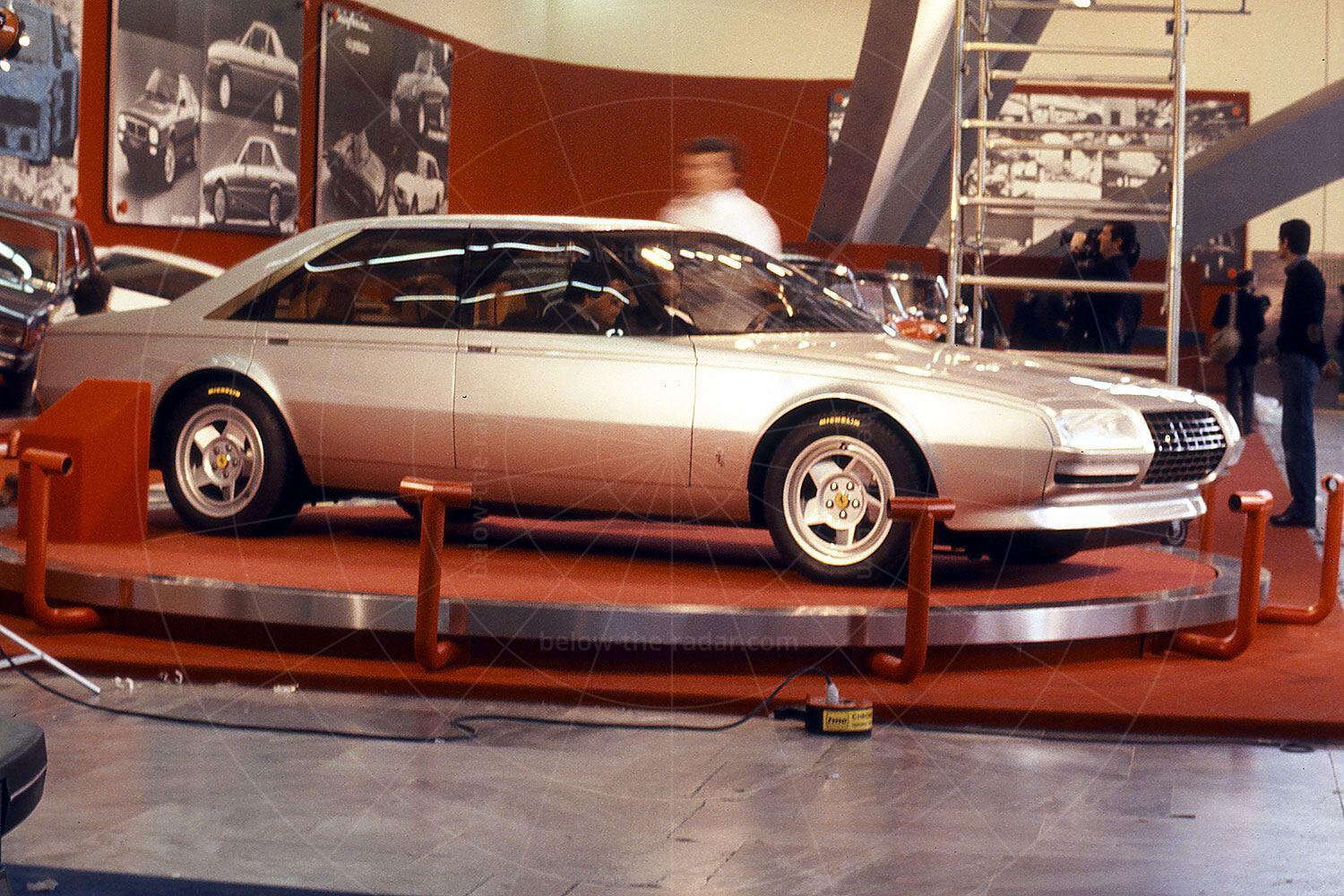

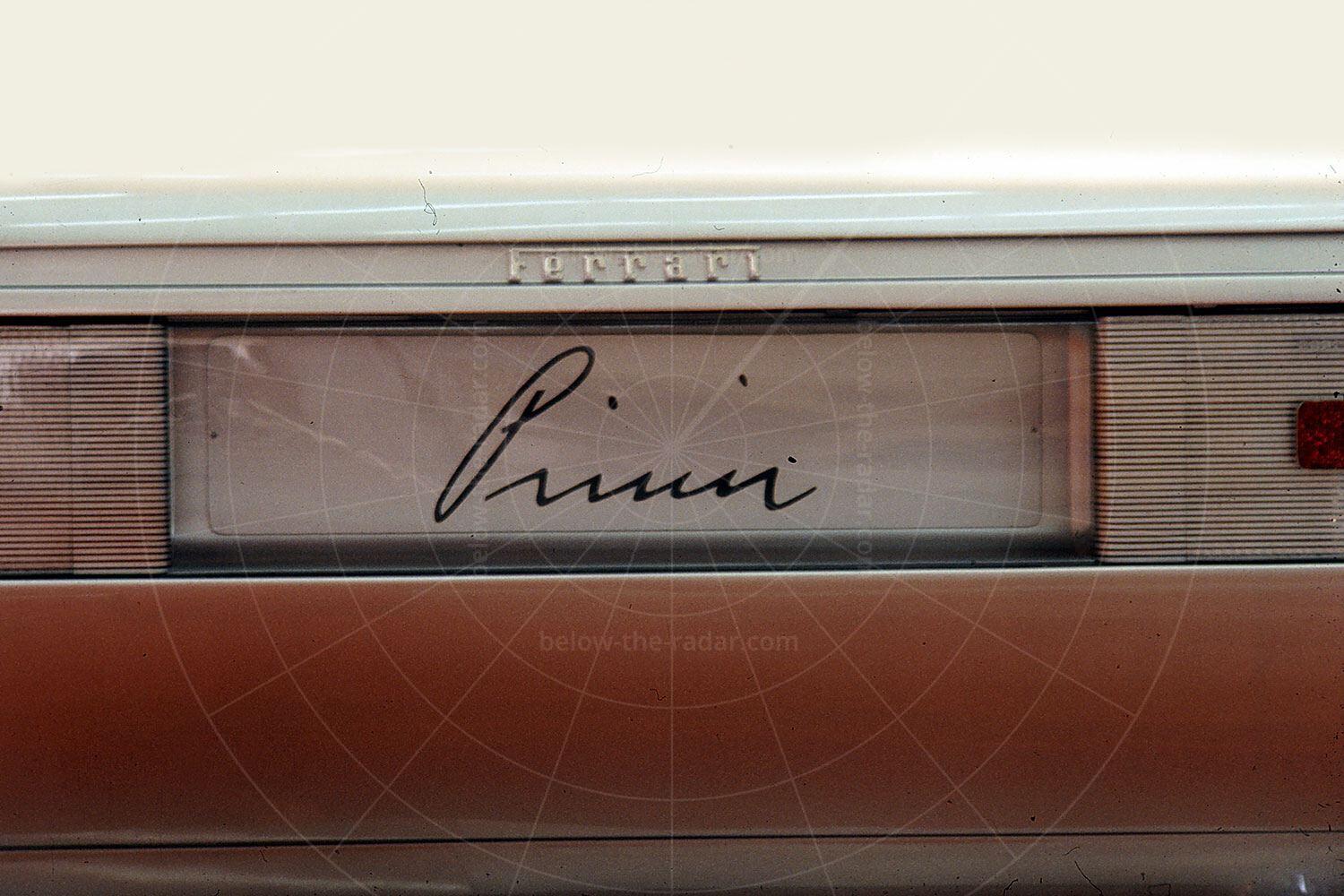

Unveiled by Pininfarina at the 1980 Turin salon, to celebrate the carrozzeria's 50th birthday, the Pinin took its name from the founder of the mighty styling house that had already collaborated with Ferrari on so many tipos. Battista 'Pinin' Farina had set up a coachbuilding firm in Turin in 1930 and in 1952, five years after Ferrari had built its first car, the first Pininfarina-bodied Prancing Horse was unveiled – a 212 Inter cabriolet based on chassis #0177 E.

Over the coming decades a raft of Pininfarina-designed landmark Ferraris would reach production, but the Pinin would prove to be still-born. Some were disappointed that the car didn't reach production, while others felt Ferrari had made the right decision. After all, four-door saloons are just so mundane – a concept that's completely at odds with Ferrari's exciting ethos. Many years after that Turin salon, an array of sports and supercar brands would unveil one saloon and SUV after another, but in 1980 the automotive landscape was very different from now. If Ferrari had built a car for plutocrats to be chauffeured around in, the Pinin would surely have been deserving of the Prancing Horse badge; this was one cutting-edge vehicle when it was first shown in 1980. While high performance was the order of the day there was also luxury; this was a car designed to take on the very best that companies such as Maserati, Rolls-Royce, Aston Martin and Mercedes had to offer.

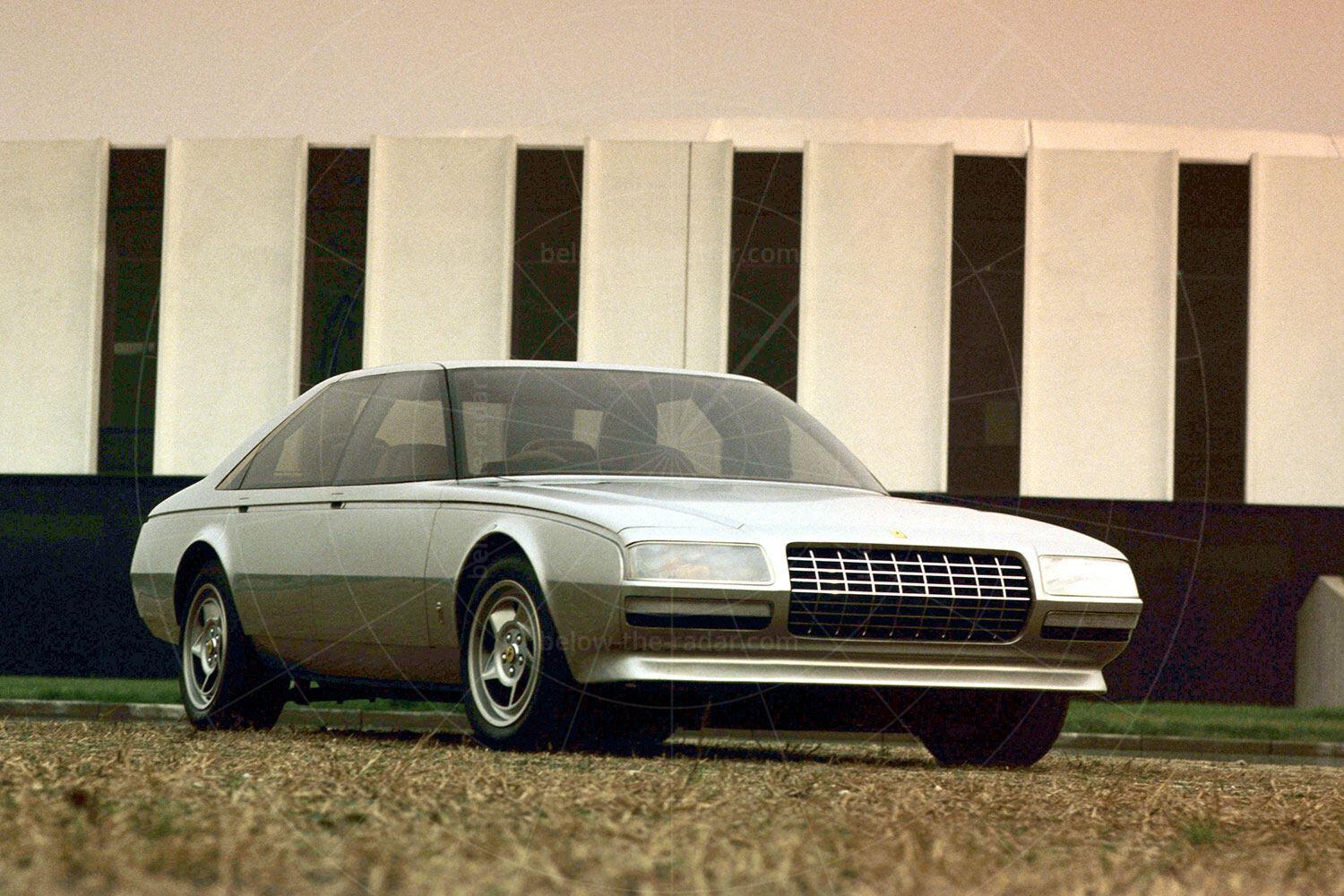

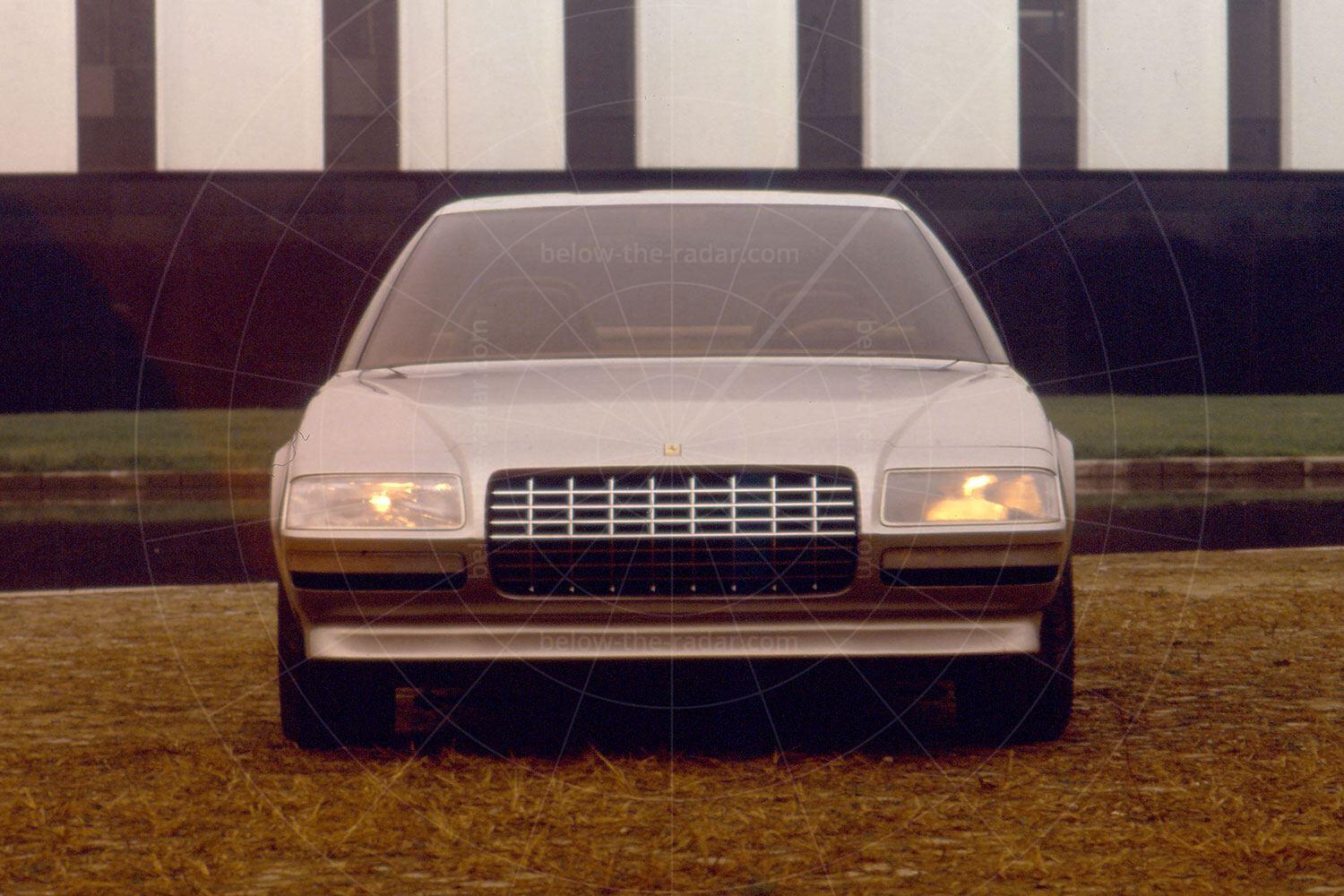

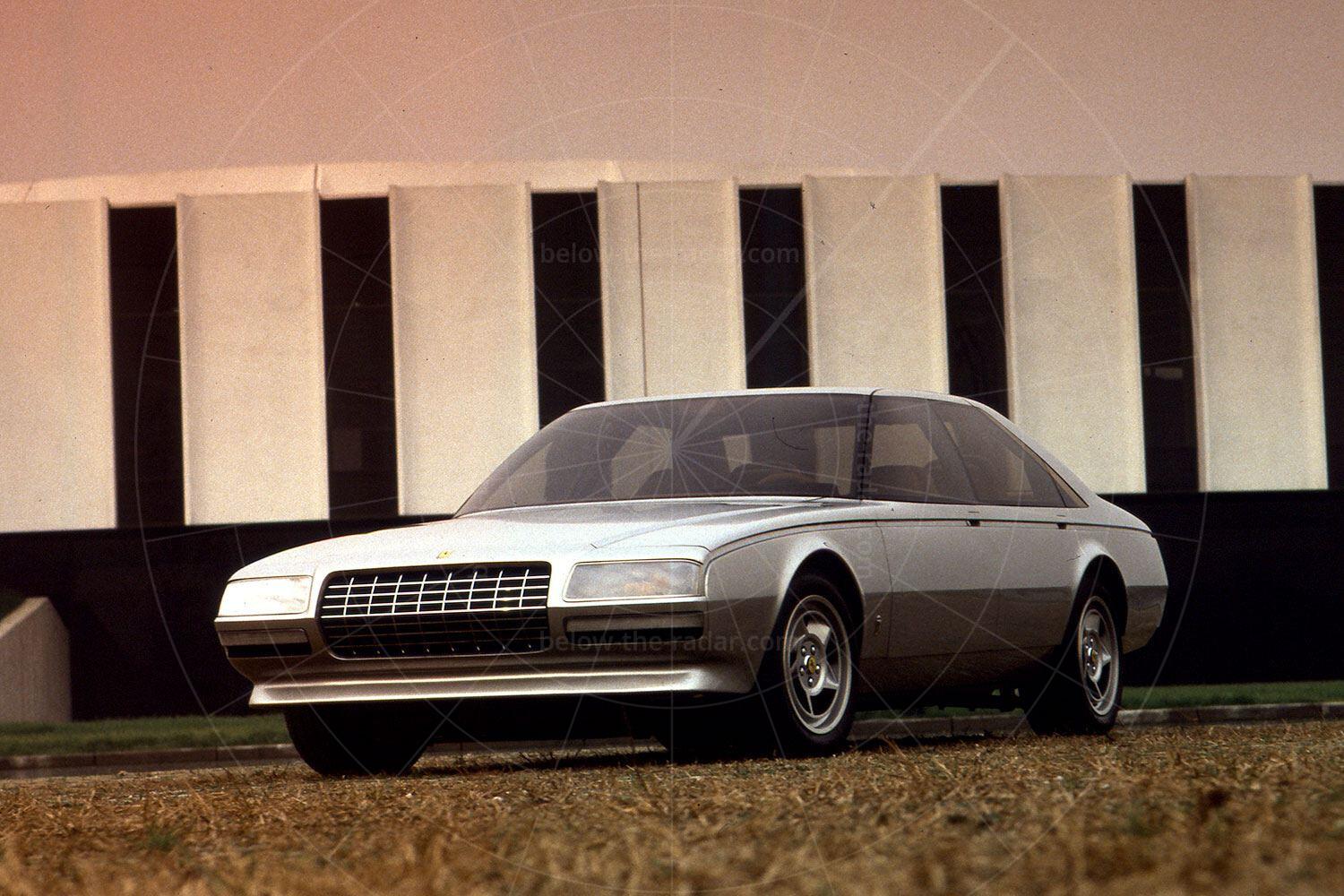

At the time the world was on the cusp of an automotive design and technological revolution. With electronics becoming increasingly common, it was possible to incorporate ever more luxury features of the type that we now take for granted. The hard-edged wedge shapes that had proliferated throughout the 1970s were also being replaced by softer lines, and it was the Pinin's exterior design that got most potential buyers salivating, as it was somehow futuristic yet discreet at the same time. The lack of any Ferrari saloon heritage meant it wasn't easy to incorporate traditional marque styling cues, although this was intended to be a concept that looked forward rather than back. Aside from Ferrari’s familiar egg-crate grille, there was little to give away the fact that this car wore those prancing horse badges.

The only other obvious Ferrari reference was the choice of wheel; the five-spoke alloys offered a nod to Ferrari’s production cars, but for the Pinin there was a twist – literally. Each spoke was twisted to turn it into a blade, which was more eye-catching while also being functional, as the blades fed cooling air to the brake discs.

Leonardo Fioravanti was responsible for the Pinin's design, working in conjunction with Diego Ottina who came up with the initial silhouette. The most striking thing about the Pinin was its flush glazing. It would be another couple of years before Audi introduced its ultra-slippery 100 saloon, with a drag co-efficient of just 0.30; the Pinin's Cd was closer to 0.35. To accentuate its slippery shape the glass was heavily tinted so that the pillars could be disguised; it was meant to look as though there was one continuous sheet of glass all round, achieved by bonding the glass to black-painted pillars. The effect was certainly striking if rather flawed, as there was no way of opening any of the windows. The windscreen wipers were hidden away behind a retracting flap at the base of the windscreen when not in use, while the door handles were flush too, hidden within a recessed belt line that ran the length of the body.

That striking grille was flanked by 'Homofocal' headlights developed by Lucas. These incorporated multi-reflectors to produce a much brighter light at night; until now, most headlamps were almost as tall as they were wide. But with the Pinin, much lower, sleeker lighting was possible which produced more light than conventional alternatives; such a design was the ideal substitute for the pop-up lights more usually seen when a low bonnet line was required. Meanwhile, the Carello-made rear lamps were also much brighter than usual, yet when they weren’t illuminated it was hard to tell that they were light units at all. Known as High Contrast illumination, the whole of the Pinin's back panel could light up, but otherwise everything remained body colour.

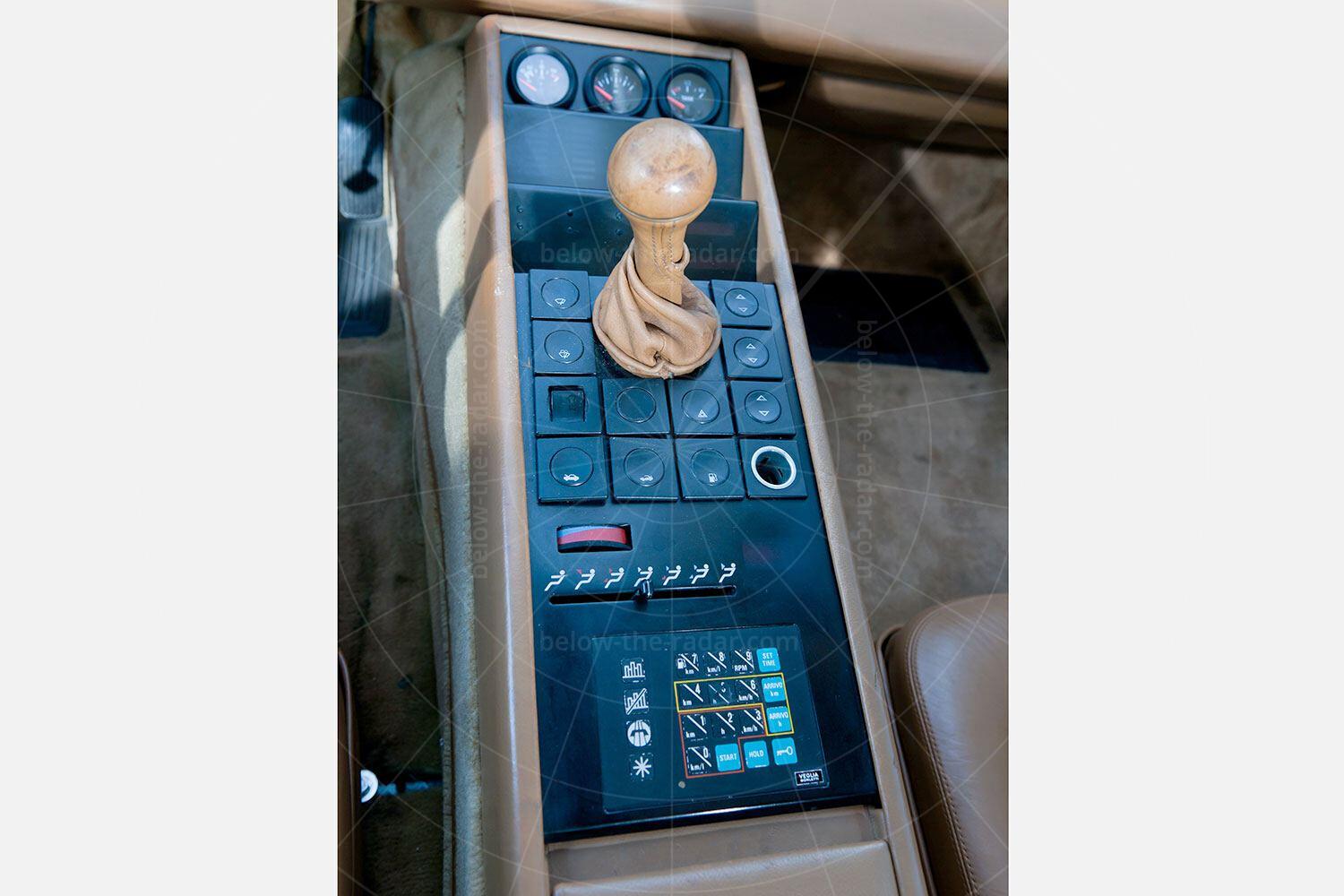

The interior looked just as high-tech as the exterior, thanks to the extensive use of LED instrumentation. As a result, until the engine was fired up the displays all remained gloss black – at which point they’d light up like Christmas trees. With Aston Martin having unsuccessfully tried to introduce the world's first all-digital dash in its Lagonda saloon, whether or not the Pinin's set-up would have been received with enormous suspicion will never be known, but it was undoubtedly cutting-edge.

Inside the Pinin a computer provided information on fuel consumption, average speed and distance along with a countdown in miles and time for a pre-programmed destination. There was plenty of luxury too; rear seat passengers got a telephone and their own radio complete with headsets, while climate control ensured the cabin temperature could be maintained regardless of how hot or cold it was outside. The two individual rear seats could be reclined independently of each other, while the two front seats had a memory function for pre-sets to be stored.

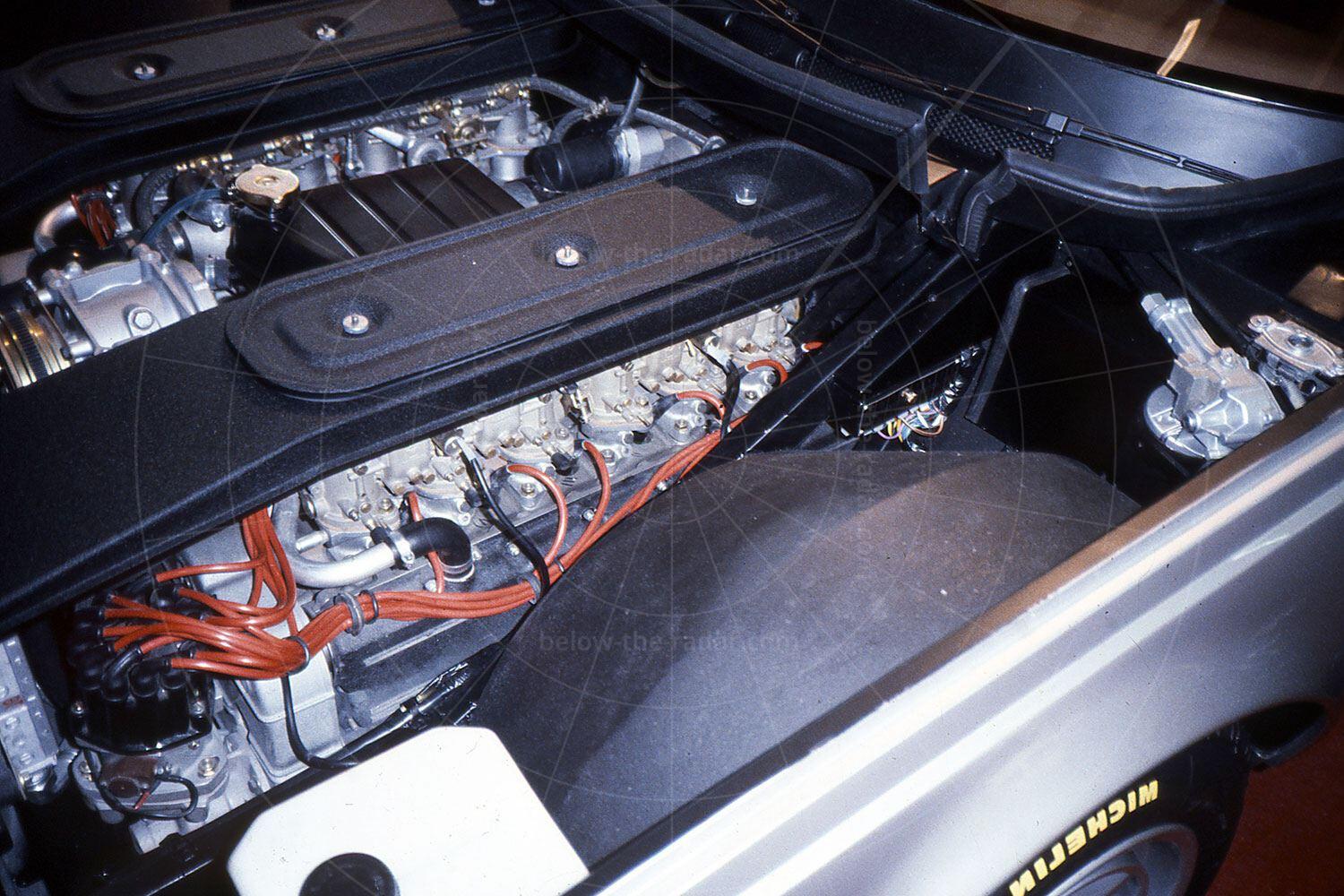

Pininfarina's vision to create an ultimate luxury express meant something impressive was needed in the engine department. After all, if the Pinin was to compete with the world's best it needed power and refinement, so what better than a 12-cylinder engine? It just so happened that Ferrari had the ideal powerplant; its 4943cc flat-12, as seen in the Boxer, which could be mounted low in the nose to ensure a low bonnet line. But in the Boxer the engine is mounted above the gearbox and the Pinin's low bonnet line didn't allow for this, which is why the 400's transaxle was used instead. While the concept's transmission was a five-speed manual unit, any production car would have had to be offered with an automatic option, with the 400's GM-derived gearbox being the obvious choice. The rest of the running gear – the brakes, steering and suspension – were all borrowed from the 400.

Whatever engine was fitted to the Pinin it would have to be capable of at least 150mph. Its key rivals such as the Mercedes 500SE, Jaguar XJ12, BMW 735i, Bentley Mulsanne, Aston Martin Lagonda and Maserati Quattroporte were all capable of around 140mph and the Ferrari would need to be faster, simply to put some distance between itself and those alternatives.

But it wasn't hitting any performance targets that scared Maranello – it was getting the quality right. Ferrari's two-door cars focused on performance, with ultimate quality allowed to be less of a priority. The company didn't have that luxury where any four-door model was concerned, because buyers would be more interested in quality than outright pace. Competing with sports cars from Maserati, Aston Martin and Lamborghini was one thing, but taking on brands such as Mercedes and Bentley meant a whole new level of fit and finish was required.

The Pinin prototype aroused a lot of interest at the Turin salon, and when it was shipped over to the US for customer clinics the car performed well. Two years after its unveiling there was still unofficial talk of the Pinin making production, with rumours persisting that it would be on sale by 1984, priced at £40,000. That would have made it more costly than any Jaguar or Mercedes, but cheaper than an Aston Martin or Bentley/Rolls-Royce. There was talk of 360 cars per year being made, each one capable of 160mph.

Had the Pinin made production a few changes would have been required, extra ground clearance a longer wheelbase and a higher roof line being just three. Production cars would also have to be runners – whereas the concept wasn't, at least when it was unveiled.

After the Pinin had returned from its customer clinics in the US, it returned to Pininfarina where it was displayed in the company's museum. By the late 1980s it was just another old concept that had served its time, but in 1993 the car got a new lease of life when it was bought by Belgian Ferrari importer and collector Jacques Swaters, to bolster his collection of priceless Prancing Horses. Even though the car didn't run he registered it on the island of Guernsey, where it was allocated the plate '20263'.

By 2008 Swaters had reached the ripe old age of 82, and he decided it was time for someone else to enjoy some of his cars. To that end he entrusted RM Sothebys to sell the Pinin, which at this stage was still a non-running mock-up – but it still achieved a €176,000 hammer price in the May 2008 auction. The buyer was Gabrielle Candrini, manager of Maranello Purosangue, purveyor of some of the world's finest historic Ferraris and based near the Ferrari factory.

While Swaters was happy to merely own a piece of history, Candrini wanted much more. His mission was to turn the Pinin into a fully driveable road car and as you would expect of someone in Candrini's position, he had the contacts, the cash and the knowledge to do just that. To that end he enlisted legendary Ferrari engineer Mauro Forghieri to turn the Pinin into a runner – which would prove to be a lengthy and costly exercise.

Forghieri started by acquiring a Testarossa engine which was adapted to work with the transmission, before the electrical and cooling systems were sorted out and a fuel tank fitted. When the car had initially been unveiled there was talk of self-levelling suspension being fitted, but this was never set up to work properly as it didn't need to with the concept being a non-runner. Candrini was insistent that if the car was finally going to be driveable, the self-levelling suspension would also have to operate as originally intended. It was getting this to work properly that would prove the biggest challenge in converting the Pinin from show star to road runner.

By March 2010 the Pinin was at last driveable under its own power, a full three decades since it had first been unveiled. But having finally turned the concept into a fully fledged car, Candrini decided it was time for someone else to enjoy the fruits of his labours and he consigned the car to auction in October 2010. The Bonhams sale was held in Dubai and the reserve was set at €1,000,000, at which point the Pinin was priced far too optimistically to garner any interest. A year later, in October 2011, RM Sotheby's was asked to sell the car, this time with a guide price of €480,000-€550,000 – and it still failed to sell. The Pinin returned to Maranello Purosangue from where it was sold to a US-bsed enthusiast, who hopefully now uses it at least on an occasional basis, although it appears to have disappeared from sight.

| Vital statistics | |

|---|---|

| Debut | Turin, 1980 |

| Designer | Diego Ottina & Leonardo Fioravanti |

| Engine | Front-mounted, 4942cc, V12 |

| Transmission | 5-speed manual, rear-wheel drive |

| Power | 360bhp |

| Torque | 332lb ft |

| Top speed | 180mph approx |

| 0-62mph | 6.0 seconds approx |