On 8 April 2005, MG Rover was taken into administration, bringing to an end an era of mass production at Longbridge. This event was extraordinary in its suddenness and the traumatic effect it had on the local community. Generations of families had worked at ‘The Austin’ not just in the manufacturing areas but also in the design studio, the offices, sales and publicity, medical facilities and canteens. Outside its gates an extensive network of suppliers, shops, pubs, clubs and community centres fed on its existence. It was just short of a century since Herbert Austin had identified Longbridge as the ideal place to set up his own enterprise and centenary celebrations were too far advanced to cancel. In a few more months, total factory production would have reached the landmark of 15 million cars.

There were many warning signs in the months preceding the collapse that all was not well, and suppliers were becoming increasingly nervous, resulting in parts shortages which were hampering day-to-day operations. After only a week, on 15 April, the majority of the 6000 workforce was made redundant, an event which has been commemorated each year since, at the Pride of Longbridge event in Cofton Park, opposite the Longbridge factory, in mid-April.

During the summer which followed MG Rover's collapse, the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust was given permission by the Administrators to make a historic record of the factory in all its aspects before it was sold on, which occurred just over three months later when the Nanjing Automotive Company purchased the remaining assets. The survey was undertaken by me, a professional archivist, with support from the Vicar of Longbridge, Colin Corke, who was both a chaplain to the factory and a volunteer in the archive. It was not an easy task. First there was the sheer scale of the factory site, not to mention its poor state of repair by now. Some indication of its size was the fact that during its history it had a sequence of entrance gates named from A through to W, though by 2005 only a handful of these were still open. This was compounded by the manner in which it had closed, which was far from normal. A factory closure is usually a controlled event which takes place in an orderly way over many months, sometimes even years. At Longbridge, the workforce was locked out overnight and stalled production hung on the assembly lines throughout the summer while the company’s affairs were wound up.

It was a big responsibility and what we found initially was bleak. The rolling road at the end of the final assembly hall should have been full of activity with finished cars being driven off the production line to go through final checks before being released to distributors and dealers, but it lay empty and silent. People had walked out of their offices to go home, leaving paperwork on their desks and whiteboards filled with notes for upcoming meetings; tools lay on workbenches, overalls hung in locker rooms, wall calendars were stuck on April, lottery syndicate numbers lay around unchecked; in the restrooms, mouldy sandwiches were abandoned on the tables and the smell of sour milk emanated from the fridges.

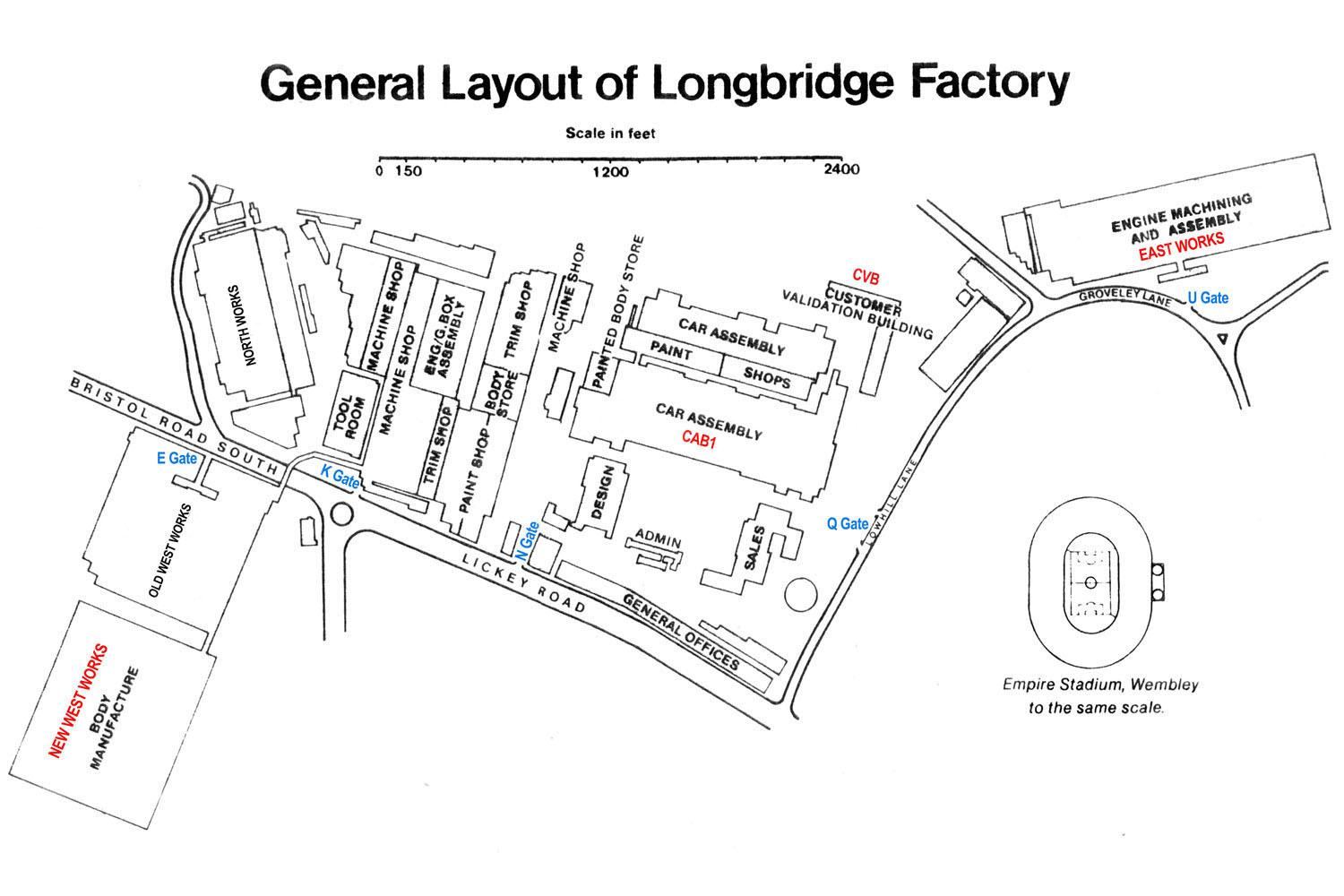

Building a car is a complex process whereby the constituent parts are each made in dedicated areas of the factory. Engines and drivetrain components were manufactured in East Works. The paint and trim shops were in the buildings clustered around N Gate. Bodyshells were welded together on automated robot lines in New West Works, which was on the opposite side of the road to the assembly halls. All these elements had to be brought together on conveyors, through a labyrinth of tunnels and bridges. Most were hidden from view except for the bridge which spanned the Bristol Road, a familiar sight to anyone driving that way from its construction in 1971 to its dismantling in 2006. The Car Assembly Building, known as CAB1, was the last stage in the process, the place where everything came together to make a complete car.

On 8 April a small number of vehicles, about 100 on each track, had been stranded in CAB1. These were sufficiently assembled to make it feasible to finish them. The Administrators decided to retain a skeleton workforce to do just this, so they could be sold as assets. Thus, the MG TF and Rover 75/MG ZT lines were restarted and the last batch of MG and Rover cars moved forward again. Initially there was a core group of 60 or so workers, but the TF sportscars moved through quite quickly, and a smaller workforce of around 30 was considered sufficient to complete the task. They were chosen for their multiple skill sets by managers who themselves were made redundant. The track carrying the Rover 25/45 and MG ZR/ZS remained stalled. Not only was there the problem of Honda’s rights in these vehicles, but there was a high volume of left-hand drive cars which limited their value as assets. Everything further back in the system – on the conveyors, in the engineering halls and trim shops, on the robot bodyshell assembly lines – remained in stasis.

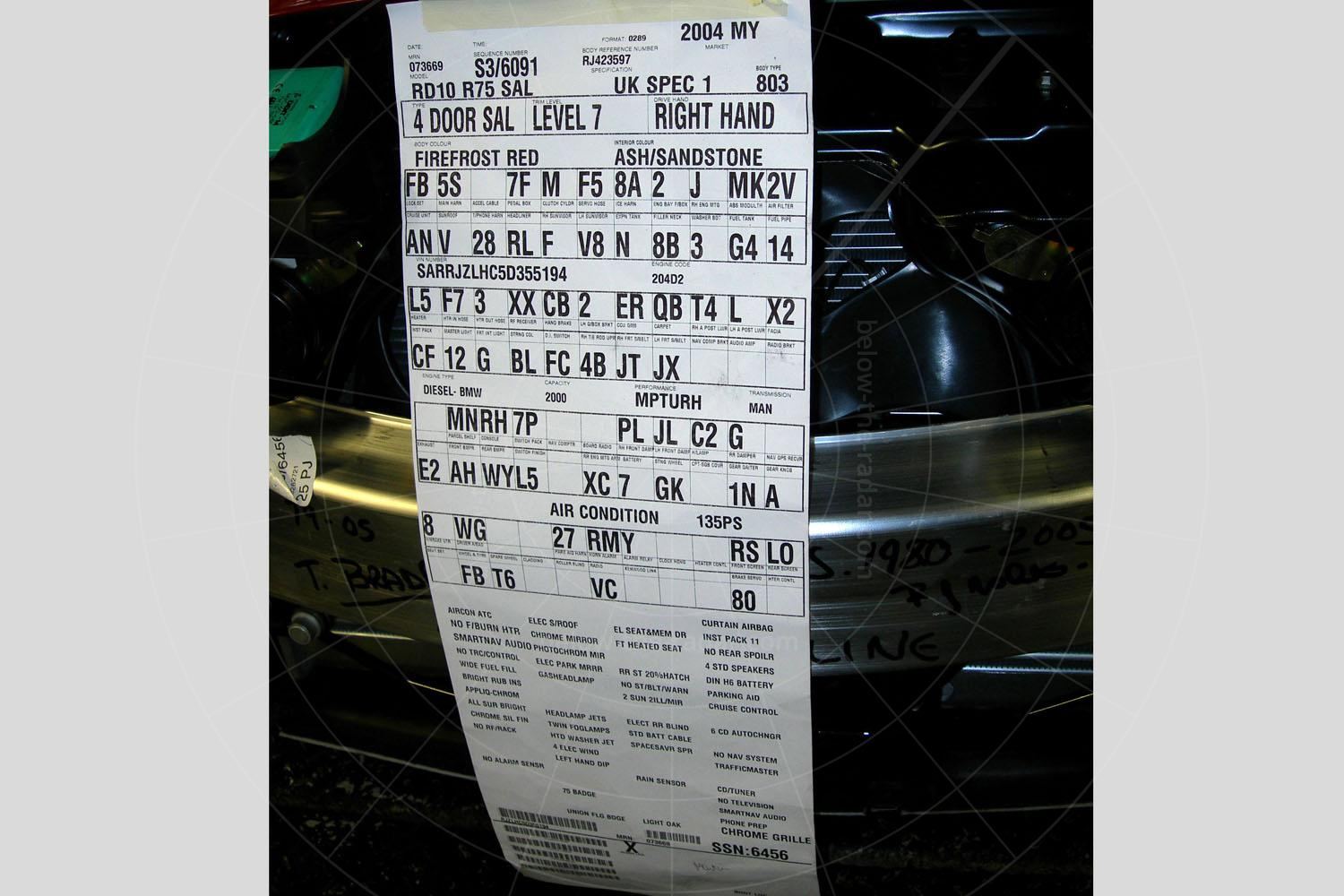

As we pressed on with our project, a story began to unfold about the ‘last car’, which was making its way down the assembly line. The build card shows it was a Rover 75 Connoisseur SE CDTi. By chance, this car had one of the highest specifications available in 2005. Details included Firefrost Red metallic paint with Ash and Sandstone leather trim, xenon headlamps, an electric sunroof, air conditioning, heated seats with electronic controls, heated washer jets, rain sensors, smartnav audio, cruise control and parking aids. Its Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) was 355194. I have a poor memory for numbers, but this is one that has lodged in my brain.

The car's significance was quickly identified by the workforce, and they pointed it out to us early on. We began to photograph it as it moved down the line through final testing and into the despatch area. Progress was slow. Normally it would take around four hours to complete the final build process but, because the automated systems and robots could not handle such a small volume of production, it took three months of hand-building to complete this final set of vehicles. Prepared parts with barcodes linking them to individual vehicles began to run out due to the just-in-time production method in use at Longbridge. This caused many complications. The seats, for example, had to be trimmed from scratch because prepared ones had run out. The windscreen was also a problem. Although there were plenty of standard screens available, the specification of #355194 required one with a rain sensor. The team had to raise a cheque from the Administrators and take one of the few works vehicles which was still road legal to go off-site and obtain one.

So that Colin and I did not miss important stages in its progress, the team working on the car would tip us off when something significant was about to happen. In this way, we were able to make sure we were in the factory at the right time to make a record of what was happening. One such day was 23 June, when we received an early call to let us know that, now the car had left its cradle and been dropped onto the moving track, some key operations were scheduled to take place. So short was the notice that Colin was busy on parish business and I had to make a hasty phone call to my workplace to say I would not be coming in, before heading off alone to the factory at 7am. It was a beautiful sunny day and the light was streaming through the skylights at the entrance to CAB1 onto the vehicles which had already made it to the end of the track, and which were awaiting their turn on the rolling road.

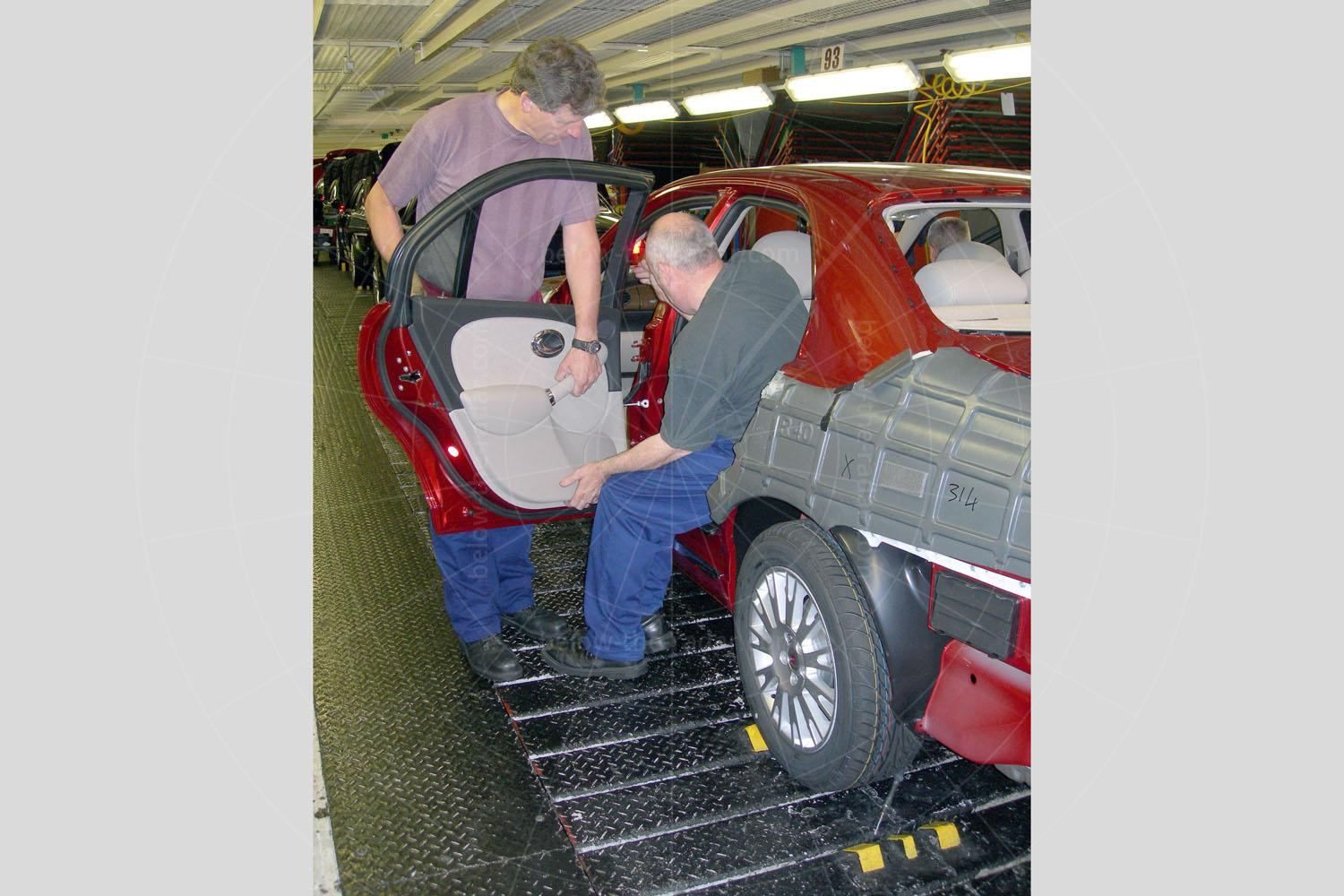

When I arrived the final track was a hive of activity, with the team busy undertaking various jobs to prepare cars and components for fitting. Of course they were not working on just a single car; those in front of #355194 also needed to be completed. By 8am they were ready to start fixing the doors which had been brought down from the level above. Like all the operations this day, this was a two-man job which had to be done manually. While the doors were being fitted, another team member started to prepare the windscreens by carefully applying adhesive to the outer rim. First, the back windscreen had to be attached and by 8.30am they were ready for the front windscreen, which was lifted with glass suckers and carefully lowered into place. Then the windscreen wipers were affixed and adjusted.

The headlamps and bumpers were still missing because of continued parts shortages. Finding the front bumper in particular took some time; it had to be the right colour, with washers for the xenon headlamps. For now, this was as complete as the car was going to get and the team took the opportunity to make their mark by signing the front and rear impact bars. Alongside their names they recorded how long they had worked at Longbridge – sometimes 30 years or more – and wrote poignant messages such as ‘God bless’. It was clear to see their pride in being part of the building of the last Rover, and their determination to do the best job possible in difficult circumstances. To the core team who remained, #355194 had became a symbol of both their own skills and what had happened to the factory.

Having started life at the back of CAB1 as a painted bodyshell in a cradle, our car was now fully built with petrol in the tank and keys in the ignition. But it still had a few hurdles to jump. First it was necessary to go through the rolling road. This was a series of booths which contained fixed roller assemblies to simulate different road conditions within a controlled environment. Once it had passed these tests, the vehicle moved on to a small building just outside CAB1 known as the Customer Validation Building, or CVB. Here, vehicles were inspected under a series of intense lights to check for body scratches or dents. Only then could it be certified as ready for dispatch.

This activity was brief. By the end of July the last cars were cleared, the tracks again went quiet and the remaining workers were also made redundant. All that was left was to sell the final few assets. The last Rover was purchased by the British Motor Industry Heritage Trust from the Administrators, and brought to the Heritage Motor Centre (now the British Motor Museum) at Gaydon in September 2005 for everyone to appreciate. It is currently on display in the Collections Centre, while the build card is preserved in the archive. The signatures and messages are still there, though hidden from view under the bumpers and seats. To outward appearance it may seem like just an ordinary car of the period, but its significance in the history of the British motor industry is hard to overstate.