History is littered with promising specialist sportscars that fell by the wayside, but the Unipower GT was more deserving than most. Acknowledged as one of the most thoroughly engineered and best-built low-volume sportscars of the 1960s, just 71 Unipower GTs were built between 1966 and 1969, but the number could have been far higher if the company had been better managed.

The Unipower GT's instigator was Ernie Unger, who loved what small cars could offer, from great agility to low running costs. While cutting his teeth at Lotus in the Fifties, before working on the Imp project for Rootes, Unger had a vision of a mid-engined road car that was great to drive, light and affordable – to buy as well as to run. In 2008 Unger told me: “I had tremendous enthusiasm for the beautiful cars of Carlo Abarth – but they were costly and didn’t handle that well. Most contemporary specialist British cars were dynamically far superior; I couldn’t see anybody who had married fabulous looks with a really superb chassis, so I set out to change that”.

Unger had been sketching his ideal mid-engined sportster for years, but was stuck for a powertrain; the key to a viable project was to use proprietary parts where possible. That meant using an engine, transmission, brakes and steering from a mainstream production car – but which one? The solution came when Rootes acquired a Mini in 1959, as a comparator car. Unger relates: “My job was to analyse rivals’ cars, and as soon as we got a Mini on the ramps I knew this was it; the proven and compact A-Series engine and combined transmission in a transverse arrangement, was clearly the way forward”.

Unger knew that containing costs was crucial for any project to be successful; his background in car production had provided the necessary skills to trim costs without cutting quality. Indeed, once he’d moved from Rootes to Ford in 1962, it was Unger who famously dissected a Mini, establishing in the process that BMC was making a loss on each one.

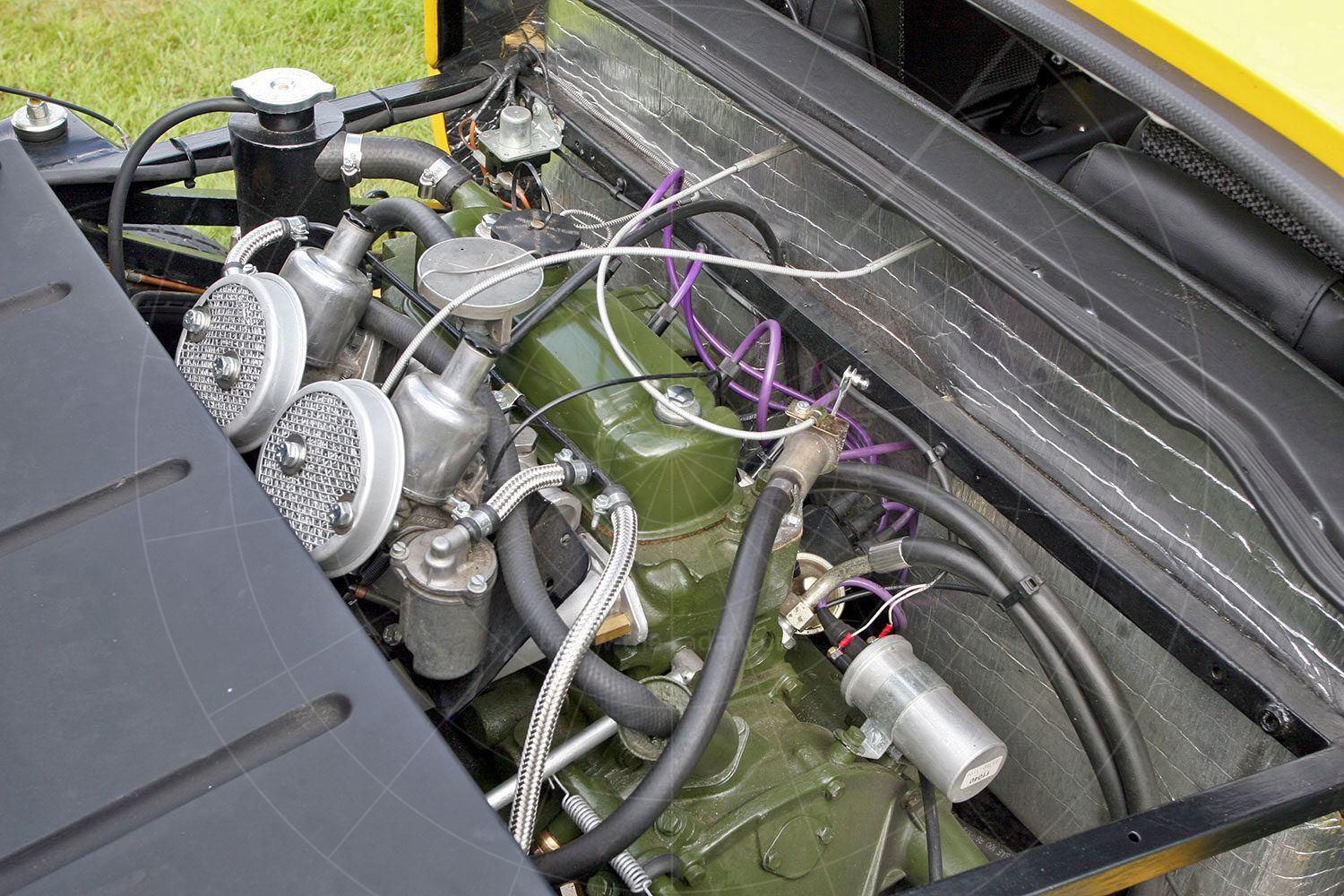

A chance conversation at Goodwood with racing car designer Val Dare-Bryan proved to be the project’s turning point; Dare-Bryan had also been thinking about producing an affordable mid-engined sportscar. At that time, Dare-Bryan was designing Attila racing cars for Roy Pierpoint. He recalls: “By early 1964 we’d built a rolling chassis with Mini 850 power, which Tony Lanfranchi drove round Brands Hatch for us. Tony was enthusiastic about the car’s potential, after a day of thrashing it around the track. Considering the hardware represented an investment of just 300 quid, we didn’t do badly”.

While Dare-Bryan designed the chassis, Unger sorted the exterior design by enlisting some professional help. Constantly in the Ford styling studio as the GT40 was being penned, Unger persuaded one of the team to lend a hand. That designer was Ron Bradshaw, who was moonlighting from the GT40 project when he drew the Unipower GT; Bradshaw's identity was kept a secret for decades.

While Bradshaw was doing his thing, a second rolling chassis was constructed, on to which Peel Brothers grafted a hand-built alloy bodyshell from which the moulds were later created; this would prove instrumental in persuading BMC to provide the necessary running gear. Says Dare-Bryan: “We were invited to lunch with Issigonis, who drove the car and was in raptures over it. He loved the mid-engined layout, but was disappointed that we’d not fitted Hydragas suspension. We had no choice; the suspension stiffness was critical, and we could get steel springs supplied exactly to our specification, for hardly any money. A bespoke Hydragas system would have crippled us financially”.

The next step meant major expenditure; buying production capacity and commissioning jigs and moulds for small-scale production. Unger was friends with Tim Powell, owner of fork-lift truck and agricultural four-wheel drive manufacturer Universal Power Drives, or UPD. Powell had just invested in a second factory which was being under-utilised; when Unger showed Powell the alloy bodyshell he immediately agreed to get involved.

With the necessary backing found, the body moulds and chassis jigs were constructed, so work could start on the first glassfibre prototype. Unger’s experience with Rootes and Ford paid off here; things progressed swiftly and relatively painlessly. So much so, that the car was ready for Olympia’s Racing Car Show in January 1966 – but the car had no name. Hustler was initially chosen, but this was adopted for UPD's fork-lift trucks so an alternative was needed. Racing Car Show organiser Ian Smith was keen to send the show programme to press and needed confirmation in a hurry, so he asked why they didn’t just call it the Unipower GT, knowing that UPD already had the Unipower name registered. Problem solved.

At the show the Unipower GT went down a storm, with enough orders placed to get production well under way. Marketing was minimal and unnecessary; from the outset the factory couldn’t cope with the flood of orders. Rave reviews in magazines worldwide ensured a steady flow of enquiries from overseas, with buyers from Spain, Switzerland and the US all placing orders, attracted at least in part by the Unipower being dubbed the 'mini-Miura' by the press.

Says Unger: “There were two types of buyer for the Unipower GT; the first wanted to use the car on the track – which is a measure of just how good it was dynamically, as we designed it purely for road use. The second type of buyer was the one who bought the car for road use. These were the connoisseurs; the sort of person who might otherwise have bought an Abarth, as the GT wasn’t especially cheap. Most customers bought a GT as a second car, although when Peter Sellers placed his order he had quite a collection of other cars in reserve!”

With a launch price of £950 for the 998cc edition, or £1150 in Cooper S 1275 spec, the GT was good value, but out of reach for many. It was also more costly than the £1107 Austin Healey 3000, while an open MGB was just £855, with a closed one priced at £998. These cars were properly supported with a dealer network, but buyers who weren’t so fussed about that could choose numerous other specialist routes, such as the £1085 Elva Courier MkIV, £699 Turner 1500 MkIII or £1060 Gilbern 1800GT.

The real thorn in UPD's side though was the Lotus Elan; the company already had a name and dealer network, while the car was perceived as dynamically perfect – and it cost just £1179 in open-topped form. To keep the price down Unipower offered the GT less its engine so it could be sold as a kit, so the buyer didn't have to pay purchase tax. Although as Unger now admits: “Most customers received a fair bit of factory help finishing their cars!”

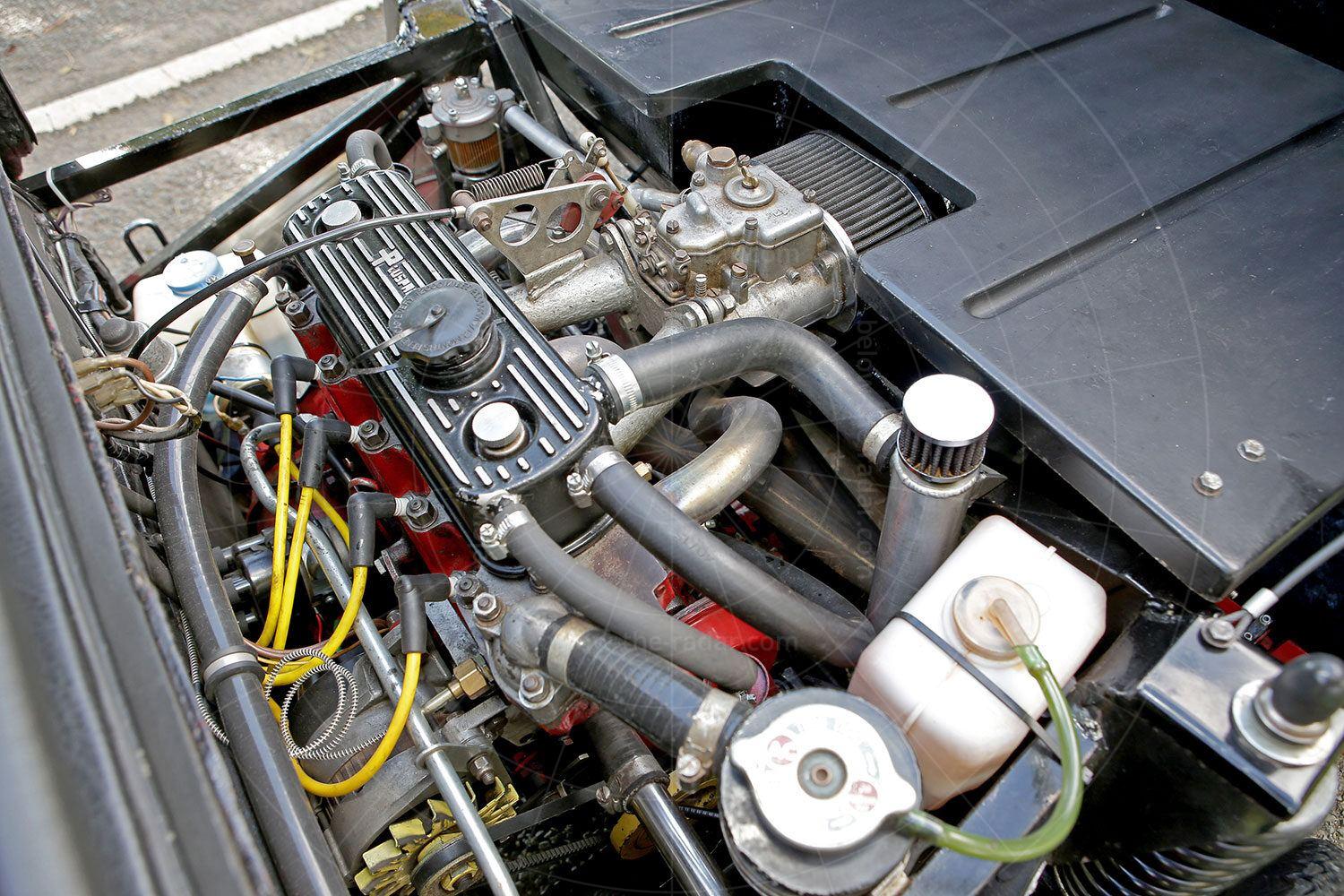

Up to this point the project had come together swiftly, but there was still much development work needed before cars could be delivered to eager buyers. The first Unipower GT (the red one pictured here, now owned by Tim Carpenter) was registered in July 1966, but the development process was slowed at least in part because Ernie Unger retained his job at Ford.

Says Unger: “The design was essentially right, but refinement was necessary. For example, we initially kept the radiator with the engine, but this led to overheating so we moved it to the front of the car. As a result we incorporated a duct so the radiator matrix also acted as the cabin’s heater – something that’s never been done since, even though it worked brilliantly [Tim Carpenter would beg to differ on this point…]. We also swapped the wind-up windows for sliding units, as the glassfibre doors could flex, leading to sealing problems, while the gear linkage design needed a lot of effort. Overall there were surprisingly few problems though; things were helped enormously by using industry contacts to get things right from the outset”.

By the time the first customer cars were ready for delivery things were already going wrong. Instead of just building customer cars, some involved in the project were keen to keep developing the GT. Also, building cars wasn’t as glamorous as Powell had hoped; there was a constant mountain of paperwork to contend with while the Unipower GT wasn’t as profitable as originally planned. Powell’s core business had also expanded so he needed the factory space that the Unipower GT was taking up. By summer 1968 a solution presented itself, in the form of wealthy socialite Piers Weld-Forrester. He approached Powell with an offer to run a works racing team, but was swiftly turned down. However, after further thought, Powell decided to sell him the whole company; Weld-Forrester jumped at the opportunity, sealing the Unipower GT’s fate.

A fresh venture was created, called UWF and with Unger and Weld-Forrester as partners; Dare-Bryan left the company almost immediately. A revised Unipower GT was then presented, with fresh rear lights, revised interior and softer springing, while a factory was acquired at Park Royal to build one car each week. But things soon went badly wrong. Customer cars got sidelined for unapproved racing projects and financial controls went out of the window; Weld-Forrester wasn’t at all commercially minded so he saw the whole Unipower GT project as a bit of fun. While he was building costly lightweight racers – two were made – customers were waiting ever longer for their cars. So it was no surprise that within months of the Unipower GT changing hands the company had gone bust, with more than 40 outstanding orders.

Unger is sanguine about the whole thing. He comments: “My only regret is that I didn’t get more involved, to keep a tighter control on things. The car had great potential; we could have looked at alternative powerplants along with bigger wheels and tyres to give an even better ride/handling balance. We might also have done a targa edition; the original alloy bodyshell featured a removable roof panel, in case we went down that route”.

Despite the low production numbers it’s reckoned that as many as 40 Unipower GTs survive worldwide, although few are running. The inherent quality of the construction of the Unipower GT has aided survival rates, but the concept is at least as impressive as the execution. Fiat clearly thought so; the company confessed to Unger and Dare-Bryan that its X1/9 was directly inspired by the Unipower GT. With around 180,000 of those built over more than a decade, it shows just how much potential the Unipower GT had.

| Vital statistics | |

|---|---|

| Produced | 1966-1969, England |

| Number built | 73 |

| Engine | 1275cc, 4-cylinder, twin SU HS2 carburettors |

| Transmission | Four-speed manual, rear-wheel drive |

| Power | 75bhp at 6000rpm |

| Torque | 79lb ft at 3000rpm |

| Weight | 509kg (claimed) |

| Top speed | 110mph |

| 0-60mph | 9.5 seconds |

| Launch price | £1150 |

Unipower GT online resources: