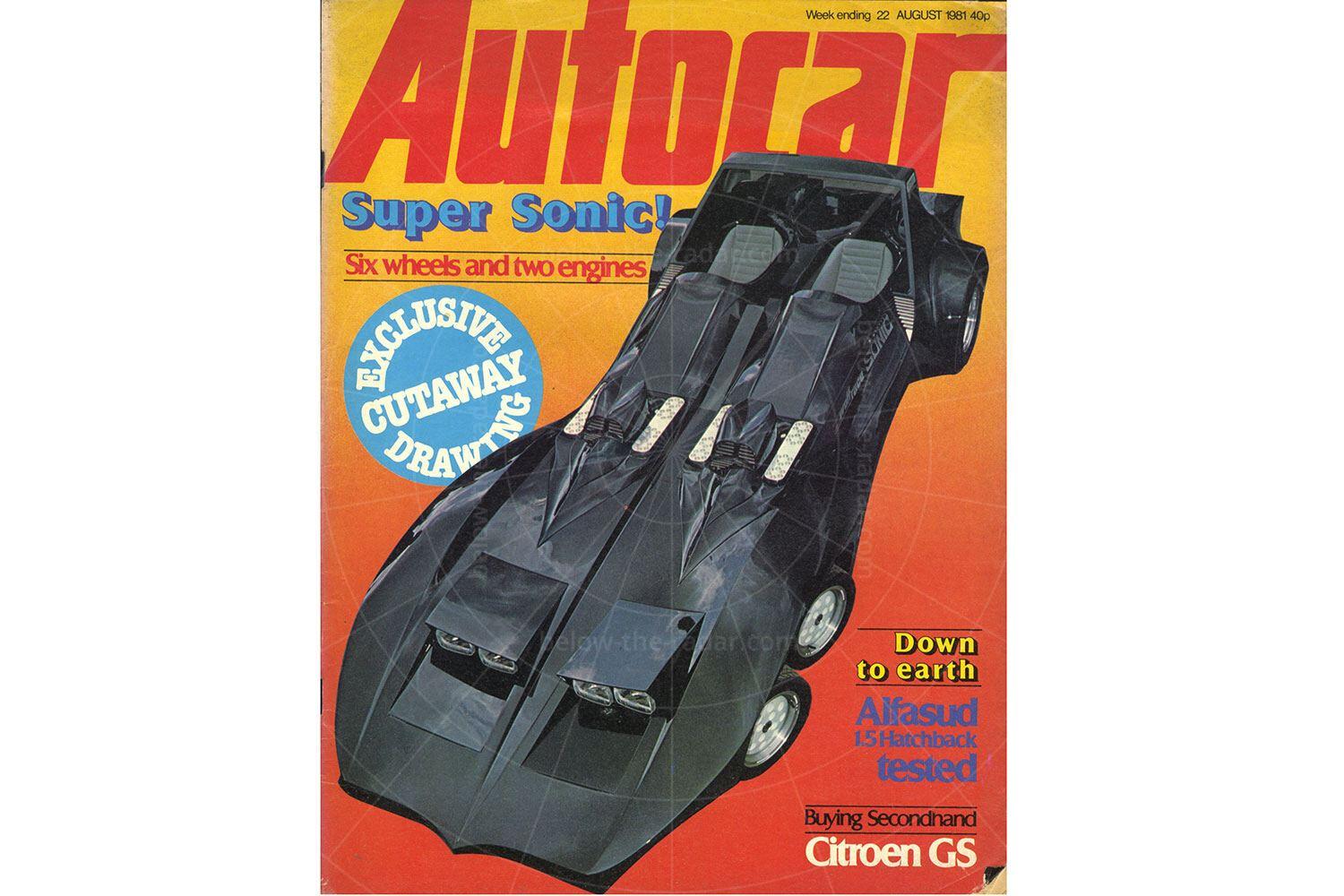

Designed purely as a publicity machine for alloy wheel manufacturer Wolfrace, the Sonic was as outlandish as they come. Commissioned by the original owner of Wolfrace Wheels, Barry Treacy, it was designed by Nick Butler who came up with a six-wheeled two-seater beast with a glassfibre bodyshell, and it was powered by two Rover V8s.

When Wolfrace introduced a new alloy wheel in 1981, Treacy reckoned something seriously special was needed to generate some column inches. Butler had been toying with the idea of a twin-engined, twin-cockpit car for years, when Treacy approached him with a view to building a fully driveable Wolfrace show car. The pair discussed the outlandish concept and Treacy was soon sold on it; any car with six wheels was bound to get more coverage in the press than something with a mere four.

The new wheel was called the Sonic and this one-off supercar would be fitted with two pairs of 13-inch wheels up front, and a pair of specially cast 15-inch rims at the back, all shod with Pirelli Cinturato P7 tyres.

As a fully running car, there were plenty of hurdles to overcome, not least of all how to keep the Sonic on the ground at the likely top speed of around 150mph. Nick Butler's custom car company Auto Imagination was expert in finding solutions to problems with its one-off creations, and they honed the Sonic's aerodynamics to stop it from becoming airborne at high speeds.

The basis for the Sonic was a tubular steel space frame with a strong centre backbone and hefty side rails to add torsional stiffness. Made from two-inch diameter cold drawn seamless steel tubing, the Sonic's chassis was immensely strong and attached to it was a moulded GRP bodyshell that would be light and easy to produce as a one-off.

One of the cornerstones of the Sonic was that it had to be futuristic, which meant it needed to be packed full of electronics. As a result the cockpits were stuffed full of buttons while the instrumentation in front of the driver was duplicated for the passenger, so they could be even more scared by what was going on around them. Each occupant got a set of liquid crystal displays which monitored the car's speed as well as the V8s' revs, water and oil temperature, the oil pressure and also the fuel level.

The two 3.5-litre Rover V8s were controlled electronically so that they provided equal, balanced power. These two powerplants were mounted side by side, ahead of the two cockpits, but behind the front wheels to aid weight distribution. Apart from the SU carburettors being ditched in favour of four-barrel Holleys, the Rover V8s were completely standard and were rated at a little over 200bhp apiece.

Naturally a bespoke exhaust system had to be fabricated which wasn't as easy as it sounds, partly because there were two V8s to work with and also because the amount of clearance between the chassis and the occupants' seats was minimal. Surrey-based TDC Components was tasked with the job and it came up with a set of pipes that fitted perfectly.

The suspension was another headache that needed some ingenuity to get right; the solution was a rear set-up based vaguely on the Jaguar E-Type's. On each side there was a mild steel upright which was machined to take Jaguar spindles, bearings and flanges. Lower wishbones were combined with fixed-length driveshafts which acted as the upper wishbones, and there was a single radius rod on each side, with everything topped off by twin coil spring and damper units per wheel.

The front wheels (all four of them) were independently suspended with unequal-length upper and lower wishbones, attached to aluminium uprights which carried Triumph Dolomite spindles, bearings and wheel flanges. Braking front and rear was by 10-inch Lockheed ventilated discs with Tyrrell four-pot callipers.

So far so good, but it was the steering that needed some extra ingenuity. The first problem was that the twin V8s got in the way of the steering column, the second was that there were four wheels to turn instead of just two. Then there was the fact that the driver's cockpit was so compact, that the 11 ½-inch steering wheel was too big to allow anybody to get in and out. The solution to this latter problem was to fit a sliding splined steering column with an assortment of universal joints, so the steering wheel moved up and out of the way as the cockpit fairing was opened. The other problems were solved by fitting various spiroid gearboxes and universal joints, which fed the steering input around the V8s and to a Rover SD1 rack.

If the steering was a nightmare to solve, the drivetrain was even more so. The solution was to duplicate everything, which meant two gearboxes, two propshafts and two differentials, one normal and the other a limited-slip item. The two Borg Warner automatic gearboxes were linked together via hydraulic tubing with modified valving so that shift signals to the driver's (master) 'box were relayed instantly to the other 'box. With no room in the cockpit for a normal gear selector, this was done via push buttons which controlled an electronic servo motor.

Then came the biggest headache of all: synchronising the two V8s so that they turned at the same revs and delivered the same amount of power at all times. The only way to do this was via electronics which in 1981 were still in their infancy, but Butler's team came up with the goods. They used magnetic sensors to measure how fast each crankshaft was turning, and the signals from these were fed to comparator units, each of which controlled an electro-mechanical servo on each throttle linkage to simultaneously speed up the slower engine and slow down the faster one. If there was a fuel or ignition fault which led to one engine cutting out, the other one would be switched off too.

The man who was tasked with making all of these complicated electronics work was London-based Michael McMartin, and it was this aspect of the Sonic that led to the biggest delay in unveiling the amazing-looking show car. But in summer 1981 the Wolfrace Sonic was finally ready to make its debut on the show circuit and to be driven by the press.

What they found was that having got into the cockpit via the electrically assisted fairings, they had to go through a 12-button starting procedure, with the left-hand engine fired up first, as this was fitted with an alternator. The right-hand engine was then started and this drove the power steering pump. Once both V8s were running the electronics then took over to keep them synchronised.

At the outset the Sonic was commissioned for £29,000 all in, but this ballooned to more like £75,000 by the time it was finished, such was its complexity – this really was a car that broke new ground. According to Treacy it was worth every penny however, as the Sonic generated huge publicity for Wolfrace before it disappeared from view when it was sold into private hands in the 1990s, only to resurface in a derelict state in 2015 on eBay, where it sold for £18,100. Since then things have gone quiet, although the car is rumoured to be with a professional restoration company ready for a big return to the show scene. We're still waiting though…

| Vital statistics | |

|---|---|

| Produced | 1981 |

| Number built | 1 |

| Engine | Front-mounted, 2 x 3528cc, V8s |

| Transmission | 2 x Borg Warner Type 65 3-speed auto, rear-wheel drive |

| Power | 400bhp at 5500rpm approx |

| Torque | 400lb ft at 2500rpm approx |

| Top speed | 145mph approx |

| 0-60mph | 7.0 seconds approx |

- More on the Sonic at AROnline.